| Green ROMandthe"Red Man"

|  |

|---|

| Green ROMandthe"Red Man"

|  |

|---|

I. Thesis: The "Indian" of Western discourse has been the creation of European ideology, from the Renaissance on. Particularly, from Rousseau on, the "Indian" has included various Euro-Romantic ideologically "use"-ful projections, including primitivism (and a concurrent nostalgia for a pre-industrial past); the related concept of exoticism; and "naturism." By this last term, I most simply mean the centuries-long conflation of "Indian" with "Nature," and "the wild," and—gasp—"the animal." (Think of such visual iconography as "Indian w/ feathers," or "The Indian & the Eagle.") . . . Or to restate this: on the Romantics' grand journey towards reprivileging "wild Nature," the "wild man" of the Americas was very much a co-opted part of that crazy ride. . . . [Late add:] Chickasaw writer Linda Hogan offers the following regarding the close historical relationship between Natives and other species as analoguous Others (read from "First People," Intimate Nature, 13). II. Antithesis: Native American tribal worldviews do include a relationship with the land and other species that is quite different—and more ecocentric—than the usually much more anthropocentric stance of Western Civ. For example, there is the more egalitarian relationship with other animals (often described as one of familial "kinship"). In Lakota, the phrases "lakota oyate," "tatanka oyate," and "wanbli oyate" translate as "Lakota people," "buffalo people," and "eagle people," respectively. Other species are characteristically viewed, then, as equals, if not superiors, to human tribal peoples. In contrast, Western discourse is permeated by this (weird, to me) binary of "humans" vs. "animals." (It's almost as if Darwin never happened.) III. The Resulting Really-Messed-Up Synthesis: 20th/21st-c. Native American writers have been really caught between a rock & hard place in terms of self/cultural representation. It is pretty much impossible to write anything "authentic" about one's traditional indigenous worldviews without consciously or unconsciously mirroring back the mainstream culture's "baggage" of projections & expectations that have accrued from several centuries of "Noble Savage" ideology. (In fact, maybe the only "authentic" pose left is one of trickster irony, as in the writings of Gerald Vizenor, whose own style is a postmodern playfulness, and whose critique of other Native writers often concludes, "This portrait is not an Indian.") Unfortunately, more well-known Native writers—such as N. Scott Momaday & Leslie Marmon Silko—have been less, uh, resistant to the general temptation of mirroring back the "eco-Indian" to their mainstream audience, of "running on the edge of the rainbow" (the oft-quoted conclusion to Silko's poem "Indian Song: Survival"). (I take credit for calling this the "running on the edge of the rainbow" school of Native poetry; Sherman Alexie has called it the "corn-pollen, four directions, eagle-feathered school.")

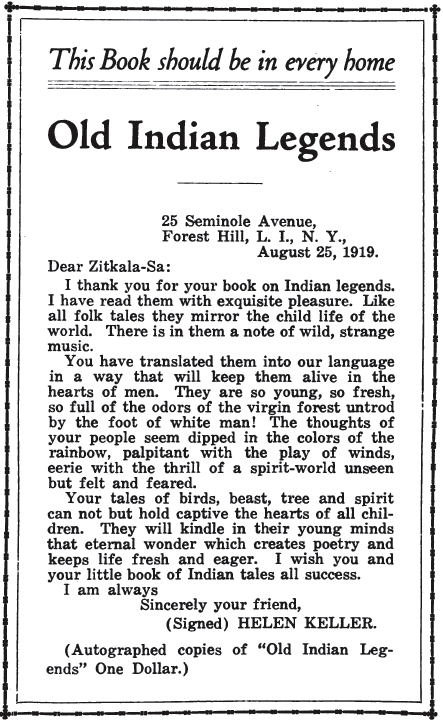

• Introductory Comments: "Huh? Tom, where is all that Indians & Nature stuff you apparently promised in assigning this reading?" . . . (Hem. Haw. Ahem.) Sorry; yes, in that regard, this text is really an exercise in "absence." What we do have, as far as ROM characteristics, are exoticism (though the "New World" setting remains the barest of backgrounds), a proto-Byronic hero nearly paralyzed with melancholia, and a very emotional/effusive style. But as w/ Goethe & Young Werther, Chateaubriand came to regret writing René, whose adolescent angst was more appreciated/embraced by readers than C. intended. Father Souël's final words to René are ultimately C.'s own attitude: "Presumptuous youth, to believe that Mankind is self-sufficient! Solitude is an evil to one who does not view it under the auspices of God" (PDF 19; "green" heretic that I am, I would simply replace "God" with "Nature" and be pretty content). As the introductory notes (PDF 2) to your online edition indicate, Chateaubriand was also no great fan of Rousseau's "Noble Savage," and moreover, like many a French Romantic, he was a devout Christian. So while the initial contrast "between the social [i.e., European] and savage ways of life" (PDF 3) is indeed telling (and ironic, given René's own shunning of white society) and while it's tempting to read the two figures of the blind Natchez Sachem [≈Chief] Chactas and the Frenchman Father Souël as a two-culture antagonistic binary, Chactas at the novella's beginning has long been a converted Christian himself, as if this were about as "wild" an "Indian" as C. can tolerate. (The allusion to Chactas' own sorrowful past [PDF 19] references another of F de C.'s novellas, Atala, in which the title character, a half-Indian [but also Christian] female, kills herself, Juliet-like, as a result of her doomed love for Chactas. I haven't read this work, but I imagine that she died "beautifully," like many an Indian in Western literature.) • "Indians"?: There is the exoticism, with May being called "the moon of flowers" by "the Savages" (PDF 3; how—uh—natural! Likewise, Neihardt, in Black Elk Speaks renders the Lakota for October as "Moon of the Falling Leaves." HOWEVER, the Lakota word wi means "MONTH" as well as "moon." Neihardt just wanted that dimestore-novel Injun-sounding hooey.). . . . Later, something of a Rousseauian primitivism occurs: "Oh: happy Savages!," René exclaims, "Why can I not enjoy the peace that ever accompanies you!" (Note how this is very similar to other ROM praise of "dumb animals.") He continues: "Your raison d'être is simply[!] your needs, and you arrive, more surely than I, at the state of wisdom, like children[!] dividing their time between play and sleep." (Helen Keller's letter a century later is little different in its primitivist condescension.) Even the Native "God" is a shadowy "unknown entity that takes pity on a poor Savage," but no doubts lacks the sophistication (& theological clarity) of the Christian one (PDF 7). . . . I can only laugh when René's final fate is to "return to his native wife, but without finding happiness with her" (PDF 20). (Given the text's racial ideology, was there ever a chance of that?!) The novella's last mention of Indians involves violence and "savagery" (an ending emphasis that would become a "formula" in Euro-American fiction); the "massacre" referred to (PDF 20) is the Natchez attack of the French at Fort Rosalie in 1729. • "Nature"?: The first extended reference includes the "peaks of the Appalachians" and the "Mississippi's waves" rolling "by in magnificent silence"; but this "calm of nature" is finally referred to as a "picture" (PDF 3), and the merely (exotic) picturesque is pretty much what it remains. (This is fitting, really, since we later learn that he has only "travel[ed] to America," to Louisiana, to escape & forget his Euro-heartbreak.) . . . Perhaps the most memorable natural image is volcanic Etna, which immediately becomes a trope for René himself, that "young man full of passion" & libido: the volcano of an "abyss yawning at" his "side" is too obviously an intrapsychic metaphor for his own unconscious seethings (PDF 7). . . . When our hero does become a Wordsworthian cavorter in the woods, a "rural exile," he seems to be merely playing at it, as a transiently adopted persona (and as ultimately a displacement for his taboo desire ["illicit passion"], of course): "I suddenly felt that a woodland life would delight me." So there he is wallowing in (I mean, enjoying) "[a]bsolute solitude, the vision of nature"—"overwhelmed by the superabundance of life." But we get few real glimpses of this superabundance, as C. falls back again upon the most clichéd nature imagery: "I embraced the winds; I thought I heard it [his 'ideal object'] in the sighing of the waters"; playing imaginative games with willow leaves, he concludes, "yet it is true that many men pin their destiny to things as worthless[?!] as my willow leaves" (PDF 9). (Needless to see, this is not a portrait of "Green Romanticism.") Later, "Migrating birds" are merely vehicles for his escapism, the wish "to fly with wings like theirs" (PDF 10). . . . VERY symptomatic (of the Western literary tradition in general?) is the juxtaposition towards the end of "the seabirds beating their wings at my window," followed immediately by "I, a poor celestial dove" (PDF 18). The REAL nature of the "seabirds" is immediately replaced by the IMAGINARY, the self-referential etherealizing of that poor overUSED trope of a "dove" (replete with its Christian theological connotations). As I claim below, "Yes, it's all about YOU, René!" . . . In the penultimate paragraph, the mighty Mississipp' returns (PDF 19), but again, only for its metaphoric use value, as an emblem of too-proud human hubris. The final paragraph's "call of a flamingo" (PDF 20) is both exoticism at work and one final "tease" of a real other species that is far too seldom in a text that obviously has other things in mind. • EGO Alienation/Melancholia: At last, the story is really all about René and the "Romantic Self." Typical of many ROM "heroes," he seems borderline bipolar (manic/depressive): His self-characterization describes an "impetuous" fellow, "[b]y turns loud and joyful, silent and sad"—and a lover of "solitude," of course, spending his youth as if caught inside a PB Shelley poem, "contemplating the fugitive clouds, or listening to the rain falling on the leaves" (PDF 4). (I'm not even counting this imagery as "Nature," they border so much on ROM cliché!) . . . No surprise, then, that he ends up, Mariner-like, "alone, alone on this earth!" And of course, like young Werther: "I decided to end my life" (PDF 10). (This would have at least saved the reader the time spent reading this novella.) • ROM Miscellanea: As one of the initial salvos of French Romanticism, the novella entails many other characteristics of what has come to be labelled Romanticism, including a privileging of the "innocence of rustic manners . . . and the delightful melancholy[?!] of the memories of early childhood" (PDF 4). There are René's proto-Byronic journeys "among the ruins of Greece and Rome" (PDF 5); there is the privileging of the Poet-Artist-Genius as a "divine race . . . . at once naive and sublime"—"like immortals or little children" (PDF 6); and, most central to the plot, we have the incestuous brother-sister-love that seems to permeate early 19th-c. ROM like an ongoing Washington, D.C. political scandal. Then there is the related idealization of women (so wonderfully "emotional" themselves, like children and "primitives"!): Amélie is loved for "the tenderness of her sentiments," her "sweetness and a propensity to dream" (PDF 11; ah). • Exhibits: [_"Lines left upon a Seat in a Yew-tree" passages_] [_Frankenstein note_]

• Introductory Comments: Educated at Dartmouth and Boston U (med school), Eastman returned to his Great Plains tribal homeland with quite a culturally hybrid outlook on things. Indeed, the very title of this book—From the Deep Woods to Civilization: Chapters in the Autobiography of an Indian—is fraught with complications & ironies, and can be read on one level as Eastman's own journey to assimilation. • Eastman's Anthropological Agenda (& his quite assimilated "1st-person-Euro-American" POV): • "Very few genuine antiques are now to be found among Indians living on reservations, and the wilder and more scattered bands who still treasure them can not easily be induced to give them up" (PDF 1). • "I secured several things that I had come in search of, and among them some very old stories" (2). • The Indian OTHER: • "Within the zone of railroads and automobiles there is, I believe, only one region left in which a few roving bands of North American Indians still hold civilization at bay" (1; note that there is no question in this chapter about who are the "civilized," who, the "barbarians"). • "[A] few northern Ojibways . . . are the present inhabitants, living quite to themselves and almost unconscious[!] of the bare pathos of their survival" (1). • "Fortunately or unfortunately[!?], the labyrinth in which they [the Ojibwe] dwell has thus far protected them far more effectually than any treaty rights could possibly do from his [the 'white man''s] almost[!] indecent enterprise" (1). • The Leech Lake Ojibways, to whom I made my first visit, appear perfectly contented and irresponsible[!]" (1). • the Ojibwe's "rude altar" (2) . . . their appellations: "aboriginal woodsmen" (3); "these sons of nature" (3) . . . their character: "very grave and reticent" (3; a STOIC race!) • "Majigabo is one of the few Indians left alive who has ventured to defy a great government with a handful of savages" (2). • "With them nothing goes to waste" (3; of COURSE: that's the first thing we ALL learned about Injuns, in the 4th grade). • A "handsome young [Ojibwe] woman" = a "daughter of the woods" (4; soon to be on a butter package in a supermarket near you!). • The Natured/"Animal" OTHER: • "The land is a paradise for moose, deer and bears, as well as the smaller fur-bearers[?!]" (1). • "[T]here are no roads through the forest—only narrow trails, deeply grooved in the virgin soil" (1; is he James Fenimore Cooper, or what?!; and so a land is "virgin" so long as it hasn't been trod by civilized humans, I guess?). • "But it is on Rainy Lake, remote and solitary, and still further to the north and west upon the equally lovely Lake of the Woods, that I found the true virgin wilderness, the final refuge, as it appears, of American big game and primitive man" (2; again the conflation of human "primitive" & the "wild"; also, the very term "game" rankles). • "The clear, black waters have washed, ground and polished these rocky islets into every imaginable fantastic shape and they are all carpeted with velvety mosses in every shade of gray and green, and canopied with fairy-like verdure" (2). • Chapter finale: a turtle "raised upon his hind feet" is scratching at the door—"his eyes shining, his tail defiantly lifted, as if to tell us that he was at home there and we were the intruders" (4; I'm giving this a big Facebook "LIKE"). • Eastman's Good Ol' ROM Nostalgia (or: Eastman "Goes Native"!?): • "I had now to follow these family groups to their hidden resorts, and the sweet roving instinct of the wild took forcible hold upon me once more. I was eager to realize for a few perfect days the old, wild life as I knew it in my boyhood, and I set out with an Ojibway guide in his birch canoe, taking with me little that belonged to the white man, except[!] his guns, fishing tackle, knives, and tobacco [and electric razor and iPhone?!]. . . . Only think of pitching your tent upon a new island every day in the year!" (3; wow; now I think I'll help found the Boy Scouts). • "the good old days" (3) • "playing Robinson Crusoe[!] on a lovely little isle" (4; translation: "I took Brit Lit at Dartmouth!") • "my last plunge into the wilderness" (4) • "[I]t all seemed weird and mysterious" (4; and—exotic).

• Introductory Comments: Although Standing Bear (Oglala Lakota) was educated at Carlisle and was nearly as successful an assimilation story as Eastman (Luther spent his last years in Hollywood, actually!), his presentation here of "Lakota wisdom" is much closer to the realities of traditional "Sioux" culture (w/ a few problematic exceptions that I note below). But of course, like Eastman, he was well aware that his audience was largely white readers of the eastern U.S., and there is no doubt a good deal of rhetorical hyperbole—in sum, ROM's "Noble Savage/Eco-Indian"—at work here. (At that time, as you've no doubt guessed by now, there was an incredibly strong push from editors & publishers to "play [up the] Indian" in such narratives/auto-ethnographies, to match the expectations of an audience who grew up on J. Fenimore Cooper and Longfellow's "Hiawatha.") The pat binary between "white" and "Indian" worldviews is especially troubling (though Vine Deloria would pretty much repeat it a half-century later), but even Standing Bear has the sense & conscience to qualify it. • Naturism: "The 'Great Out-doors' was reality and not something to be talked about in dim consciousness" (Callicott & Nelson 201:¶1). . . ."The Lakota was a true naturist—a lover of Nature. He loved the earth and all things of the earth, the attachment growing with age." He felt "kinship to [all] other lives about him" (202:¶1, 2). • Wilderness, Wild Animals, Wild People: "Only to the white man was nature a 'wilderness' and only to him was the land 'infested' with 'wild' animals and 'savage' people" (201:¶2). Elsewhere in Land of the Spotted Eagle, Standing Bear is even more to the point: "I know of no species of plant, bird, or animal that were [sic] exterminated until the coming of the white man. . . . The white man considered natural animallife upon this continent, as 'pests.' Plants which the Indian found beneficial were also 'pests.' There is no word in the Lakota vocabulary with the Englishmeaning of this word" (165). . . . [Later in our reading:] "Many times the Indian is embarrassed and baffled by the white man's allusions to nature in such terms as crude, primitive, wild, rude, untamed, and savage. [For the Lakota, in contrast,] birds, insects, and animals filled the world with knowledge that defied the discernment of man" (205:1st/continuing¶). • The Earth Is Your Mother?: "Wherever the Lakota went, he was with Mother Earth" (202:¶3). (However, this is really a cultural mistranslation. In Lakota, the expression is unci maka—Grandmother Earth! Maybe that's why I like Sherman Alexie's quip, "the earth is our grandmother and . . . technology has become our mother and . . . they both hate each other" [Lone Ranger 129].) • Wakantanka: "From Wakan Tanka [literally: "power big"] there came a great unifying life force that flowed in and through all things—the flowers of the plains, blowing winds, rocks, trees, birds, animals—and was the same force that had been breathed into the first man. Thus all things were kindred, and brought together by the same Great Mystery" (202:¶4; see also 206:¶1). ("Great Mystery" is an alt. translation of wakantanka and is much preferable to the "Great Spirit" [Black Elk/Neihardt] or even the "Big Holy" [Lame Deer/Erdoes; also Standing Bear himself: 204:1st/continuing¶]. "Wakan, again, is "power," even "energy." The first white translators were Christian clergy, however (& of course), and so "wakan" became "holy," "sacred," and "spirit[ual]": that is, it was rendered at last much more Christian-metaphysical sounding than its original meaning warranted. Also, wakantanka is a non-anthropomorphic, ungendered pure omnipresent force; and so Standing Bear's later masculine pronouns [204:1st/continuing¶206:¶1, 2] in refernce to it are also assimilationist ascriptions.) . . . What has long struck me is how close this description of the Lakota "great power" is to Wordsworth's so-called "pantheism," as described in "Tintern Abbey." I have even suspected that some early anthropologists, attempting to understand the Lakota "concept," had Wordsworth's passage (and/or similar ROM passages) mumbling in the back of their heads as they tried to describe such a truly non-Western notion! And that these early cultural translations influenced even later Native/Lakota authors. In other words, I can imagine a series of influences beginning w/ Wordsworth that lead to this very passage in Standing Bear. (Okay, you can take me away in a straightjacket now.) . . . One more piece of "evidence" that wakantanka is above all imminent/"pantheistic": "The Lakota could look at nothing without at the same time looking at Wakan Tanka" (206:¶1). (It also just occurs to me: when an "Indian" says stuff like this, it's called [primitive] "animism"; when a philosophically inclined British Romantic poet says stuff like this, it's called "pantheism"?!) • That's DEEP Ecology, Dude: "The animal had rights . . . and in recognition of these rights the Lakota never enslaved the animal, and spared all life that was not needed for food and clothing. [¶]This concept of life and its relations . . . . gave him reverence for all life; it made a place for all things in the scheme of existence with equal importance to all" (203:¶1, 2). (Note how similar this is to deep ecology's "bio-egalitarianism" and Lawrence Buell's "ecocentrism." Of course, deep ecology can very much be read as another, contemporary manifestation of "Green Romanticism.") . . . [Similarly:] "Everything was possessed of personality, only differing with us in form. Knowledge was inherent in all things. The world was a library and its books were the stones, leaves, grass, brooks, and the birds and animals that shared, alike with us, the storms and blessings of earth" (204:1st/continuing¶). (Of course, "Nature" as a "book" has a long Euro-literary history.) • Cowboys v. Indians: "I have often noticed white boys" spending "much of their time in . . . aimless fashion, their natural faculties neither seeing, hearing, nor feeling the varied life that surrounds them." (Think René, and the "Yew-tree" fellow? Or think of today's kids w/ Nature Deficit Disorder & video games?!) "In contrast, Indian boys . . . are alert to their surroundings" (204:¶1). Of course, this is a gross over-generalization, and SB soon acknowledges as much (that is, the difference is not genetic or "racial," but socio-cultural & learned): "Every true student, every lover of nature has 'the Indian point of view,' but there are few such students, for few white men approach nature in the Indian manner. The Indian and the white man sense things differently because the white man has put distance between himself and nature; and assuming a lofty place in the scheme of order of things [i.e., anthropocentrism] has lost for him both reverence and understanding" (204:¶2 [contin. on 205]). . . . But that Western culture has truly wrought some eco-damage: North America hardly "pleased the white man, and nothing escaped his transforming hand. Wherever forests have not been mowed down; wherever the animal is recessed in their quiet protection; wherever the earth is not bereft of four-footed life—that to the white man is an 'unbroken wilderness.' [I recall some of this same eco-passion in some places in Wordsworth.] But"—as we saw above—"for the Lakota there was no wilderness . . . . Indian faith sought the harmony of man with his surroundings; the other sought the dominance of surroundings. . . . [O]ne people naturally found a due portion of the thing they sought, while, in fearing, the other found the need of conquest. For one man the world was full of beauty; for the other it was a place of sin and ugliness to be endured until he went to another world, there to become a creature of wings, half-man and half-bird" (204:¶1; don't get me started on angels, and theriomorphism!). "The old Lakota was wise. He knew that man's heart, away from nature, becomes hard" (205:¶2 [contin. on 206]). (Maybe it's just me, but this sounds SO much like Wordsworth, "Yew-trees" poem et al. The last ten syllables of the sentence are even iambic pentameter!) • Exhibit: [_"Tintern Abbey" passage_]

• Introductory Comments: Note, first of all, that in this three-part sequence of Native readings, Euro-American assimilation seems to be going backwards, with Eastman sounding the most "Anglo," and Lame Deer sounding the most "naturist-Indian" (at least w/ his Red Power 'tude?!). Part of this is certainly the Native cultural revival that began in the 1960's, with the Red Power movement, et al. But you also need to be aware that this book was co-authored (at last, written) by Richard Erdoes, an Austrian-German Euro-hippie of sorts, who, as he himself acknowledges in the book's Epilogue, grew up "predisposed to love Indians" (257), for very ROM reasons, especially the 19th-c. "Noble-Savage" romance-Westerns of German author Karl May. (Thus the Ojibwe critic-scholar Gerald Vizenor can say, with a trickster wink, that "Germans make the best Indians.") In sum, much of the "Indian" anti-western-civilization outrage going on here is as much if not more the product of Erdoes' agenda as it is Lame Deer's. (Compare Rousseau's "use" of the indigenous as "foils" by which to critique Euro-civilization. Likewise, the most vitriolic passages against the wašiču [whites] in Black Elk Speaks were almost all editorial additions by John G. Neihardt—as were many of the most "eco/spiritual-Indian"-sounding effusions.) • "Let's Talk": "Let's sit down here, all of us, on the open prairie, where we can't see a highway or a fence. . . . Let us be animals, think and feel like animals. [¶]Listen to the air. . . . Woniya waken [N.B.: wakan]—the holy air . . . . [W]e feel it between us, as a presence. A good way to start thinking about nature, talk about it. Rather talk to it . . . as to our relatives" (PDF 1). • "You're UnNATURAL": "You have made it hard for us to experience nature in the good way by being part of it. . . . The only use you have made of this land since you took it from us was to blow it up. You have not only despoiled the earth, the rocks, the minerals, all of which you call 'dead' but which are very much alive; you have even changed the animals . . . changed them in a horrible way . . . . There is power in a buffalo . . . but there is no power in an Angus, in a Hereford." As for the wild foul: "you have made them into chickens, creatures that can't fly, that wear a kind of sunglasses so they won't peck each other's eyes out . . . . There are farms where they breed chickens for breast meat. . . . Having to spend all their lives stooped over makes an unnatural, crazy, no-good bird. It also makes unnatural, no-good human beings." You have" even "done it to yourselves. You have changed men into . . . time-clock punchers. . . . You live in prisons which you have built for yourselves, calling them 'homes,' offices, factories" (PDF 1; cf. Wordsworth?!: "Have I not reason to lament / What man has made of man?"!). . . . "Americans want to have everything sanitized. No smells! Not even the good, natural man and woman smell. . . . Soon you'll breed people without body openings. [¶]I think white people are so afraid of the world they created that they don't want to see, feel, smell or hear it. . . . Living in boxes . . . hearing the noise from the hi-fi instead of listening to the sounds of nature." . . . As for food, now—"buffalo guts" and wasna: "That was food, that had the power. Not the stuff you give us today: powdered milk, dehydrated eggs, pasteurized butter, chickens that are all drumsticks or all breast; there's no bird left there." . . . "Your idea of war—sit in an airplane, way above the clouds, press a button, drop the bombs, and never look below the clouds—that's the odorless, guiltless, sanitized way" (PDF 2). • The Sacredness of Life: "When we killed a buffalo," we "apologized to his spirit . . . honoring [him] with a prayer . . . praying for the life of our brothers, the buffalo nation, as well as for our own people. You wouldn't understand this and that's why we had the Washita Massacre, the Sand Creek Massacre, the dead women and babies at Wounded Knee. That's why we have Song My and My Lai now. [¶]To us life, all life, is sacred" (PDF 2). Coyotes "are our natural garbage men cleaning up the rotten and stinking things" (PDF 2-3). "But their living could lose some man a few cents, and so the coyotes are killed from the air. . . . More and more animals are dying out. . . . That terrible arrogance of the white man, making himself something more than God, more than nature, saying . . . 'The only good coyote is a dead coyote.' They are treating coyotes almost as badly as they used to treat Indians (PDF 3; N.B. the conflation of "animal" & "native" once again). • A New Ghost Dance?: "Eighty years ago our people danced the Ghost Dance," hoping that we would find again the flowering prairie, unspoiled, with its herds of buffalo and antelope, its clouds of birds, belonging to everyone, enjoyed by all. [¶]I guess it was not time for this to happen, but it is coming back, I feel it warming my bones. Not the old Ghost Dance . . . but a new-old spirit, not only among Indians but among whites and blacks, too, especially among young people" (PDF 3; this hope for a "belated" eco-regeneration that the Ghost Dance called for is a common theme among both contemporary Native authors and certain deep ecologists [Devall & Sessions]). • A New World?: Lame Deer even foresees an eco-apocalypse: "I saw this in my mind not long ago . . . . A young man will come, or men, who'll know how to shut off allelectricity. It will be painful, like giving birth. . . . [T]he machine stops and they are helpless, because they have forgotten how to make do without the machine. There is a Light Man coming, bringing a new light. It will happen before the century is over [Oops!].

• APPENDIX: The (pretty dated) critical texts that most influenced my notion of what "Green Romanticism" is:::: Bate, Jonathan. Romantic Ecology: Wordsworth and the Environmental Tradition. London: Routledge, 1991. Buell, Lawrence. The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1995. McKusick, James C. Green Writing: Romanticism and Ecology. New York: St. Martin's, 2000.

• BTW, my "word cloud" (based on word frequencies) of "Tintern Abbey"; contrast "Nature" with "I" and "my"!:::: |

| Green ROM & the "Red Man" Thomas C. Gannon Date Created: 24 October 2012 // Last Revised: 30 October 2012 < http://incolor.inebraska.com/tgannon/GreenRom&theRedMan.html > |

|---|