|

"A MOST ABSORBING GAME":Peterson's Field Guide & The New World Bird as Colonized Other --Thomas C. Gannon--

[first published in The Ampersand 11 (Jan. 2002)]

|

[I]t is hoped that the advanced student will find this guide comprehensive enough to . . . . realize the possibility of quickly identifying almost any bird, with amazing certainty, at the snap of a finger. . . . It is the discovery of rarities that puts real zeal into the sport of birding, a zest that many of us would like to interpret as "scientific zeal" rather than the quickening of our sporting blood. Field birding as most of us engage in it is a game--a most absorbing game. (Peterson xviii) |

I. Introduction: A "Natural" System

I. Introduction: A "Natural" System

Roger Tory Peterson's "Preface" to his Field Guide broaches his ornithological agenda via an anecdote of a "lad" who, "since he only saw the live birds at a distance . . . was frequently at a loss for their names." But the various distinguishing marks of the different species (ducks, in this case), the boy realized, were like "labels or identification tags"; if he were only able to systematize such markings, "he would know the ducks as soon as he saw them on the water" (v). This story supposedly provided the inspiration for Peterson's revolutionary work in popular ornithology: if one could develop a "system" that presented, in an orderly fashion, the distinguishing features of various bird species, then the identification of any particular bird viewed in the "field" would be possible for anyone with eyes, perhaps a pair of binoculars--and Peterson's Field Guide to the Birds.

Indeed, Peterson's 1934 Guide "ushered in the era of the modern field guide and formed the birdwatching interests of a generation" (Gibbons and Strom 288).{1} Its methodology supposedly provided for a complete democratization of bird identification that brought the ornithological advances of the last two centuries into the purview of "everyperson." However, the ultimately hegemonic and elitist assumptions of such a rationale open up Peterson's project to critique based upon class, gender, and even race. Just as crucially, the Guide's complicity in an ongoing discourse of power renders the book a fit subject for examining the ways in which non-human species are "othered" in a manner that allows the anxious white-male-bourgeois ego of Western Civilization to recuperate its false sense of unity and integrity. By assuming, then, a Nietzschean-Foucaultian notion of a "will to knowledge" regarding the Other (be it another "race" or another species), I hope to at last draw a parallel between the theories of colonial discourse analysis and ecocriticism that is too strong to be any longer ignored. For at last, if the subject matter of colonial discourse theory is "the process of production of knowledge about the Other" (Williams and Chrisman 8), and if the concept of the "Other" can be legitimately extended to the non-human, then the non-human Other certainly qualifies for some of the attention that has so far been given almost exclusively to socio-political human issues.

Anglo-American popular interest in ornithology began circa 1800, fostered both by a newfound infatuation with science--and "collecting"--in general and by the special "social" and symbolic status that birds had acquired through the centuries: soon "ornithology became the most popular scientific disciple," supplemented by a good many "handbooks and periodicals" for its new tag-along hobbyist public (Gaull 369). Meanwhile, this same ever-curious Western "I" or "eye" had established itself in the New World, looking around and seeing mere landscape,{2} or seeing Native Americans as little-more-than-animals ready for colonization. It also saw native animals themselves as fit fodder for the same taxonomical classification it had applied/would apply to other, human "races."{3} The West's natural-history taxonomical system initiated by Linnaeus might indeed by seen as the regime of "knowledge" behind the "power" of the actual boats and gunpowder of New World colonization, itself a "European knowledge-building enterprise of unprecedented scale and appeal" (Pratt 25){4}--and an enterprise to be continued in the gun-and-easel collecting and categorizing of 19th-century American ornithologists like Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon.

This "naturalist's narrative" of order is thus a Foucaultian discourse that has held "enormous ideological force" from the 19th century to this day (28). Before examining how this discourse is worked out in Peterson's Guide, it should be noted that the categorizing imperative of Western natural science has led to some rather questionable tenets and manoeuvres, as evidenced in the field of ornithology. For one thing, the very notion of an essentialist "species" (and the strange and awkward term "race," a synonym for sub-species) is really a mere construct, rendered continually problematic by birds' perverse habits of cross-breeding (or hybridization)--the bane of many a taxonomist. And yet every "species" is still given a two-part Latin genus+species name, as if these were the one, true "given and family names," as Pratt puts it, of an anthropomorphic "republic" (35). But nor can ornithologists even decide on the proper "hierarchal order" for the various orders and families of birds, or even which "species" belongs to which "family": each new revision of the avian taxonomy includes several (often radical) promotions and demotions in the grand Darwinian scheme of things, as an assumed synchronic essentialism is undermined by intermittent, diachronic revisions.{5} (Similarly, the human "races" continue to suffer various "Bell Curve" re-privilegings of their "essential," hierarchal status.) But most problematic, in my view, is the general homocentric view of birds as "lower," inferior beings, an attitude still universal today, whether ideologically grounded in some naive ego-anthropomorphism or in a just-as homocentric Darwinian evolutionary schema. The colonizing, taxonomical "I" thus finds ample ground for its "vision" even in such supposedly objective and scientific texts as Peterson's Guide.

II. Peterson's Guide as the "Birder's Gaze"

II. Peterson's Guide as the "Birder's Gaze"

Pratt's self-effacing "Imperial Eye" reveals itself, first of all, in the very layout of Peterson's book. Museum-like in its pairing of illustrated plates with accompanying text on the facing page [see appended plates 2-6{6}], the Guide presents itself as a "display-case" model of objectivity and transparency; characteristically, Peterson himself seems to have "no place in the description" (Pratt 32)--but for a few condescending, "power-trip" references in the text about "tyros" and "beginners." Above all, he epitomizes Pratt's naturalist whose "vision" is ostensibly "harmless," but, as we shall see, "hegemonic" (33). The bird "student," too, indoctrinated into Peterson's "field mark" revolution, is thus armed with a set of visual and verbal signifiers that determine the scope of his/her interpretations of these new-world "aborigines" with feathers and wings.

Both art and text, moreover, demonstrate a very specular attitude towards the avian: "Peterson's commitment to his visual identification system was whole-hearted" and, indeed, his system "dominates the birder using the Guide in the field" (Gibbons and Strom 298, 299).{7} As we have already seen, the Guide's goal was to allow "live birds" to be "run down[!] by impressions, patterns, and distinctive marks" (Peterson v-vi). And while Peterson's clear line drawings may appear more realistic than the highly stylized, awkwardly posed, bird paintings of Audubon, they are actually simplified to a generic fault: as he admits, "all modelling of form and feathering is eliminated[!] where it can be managed" (xix). Furthermore, it is a very black-and-white simplicity, broken up by only a few color plates: "Even color is often an unnecessary, if not, indeed, a confusing, factor" (xix). But a major factor of life and vitality, one might add, however unnecessary to a scopic will bent on sheer identification, or visual appropriation.{8}

What stands out especially in Peterson's devitalized, "museum" views of the birds is that almost all are in profile, a distancing or reification that detaches the viewer from any emotional connection with the "objects" at hand [see plates 1-2, 5-6]. (More "distanced" yet, perhaps, are the "belly-bottom" views of the hawks in flight [plate 3].) The notable exception is the Owls plate [plate 4], which thus becomes a rather haunting view, as if one were suddenly peering into Levinas's "face of the Other." One is tempted to interpret this plate as the point of supplementarity or excess in the "text," where the marginalized Other breaks through, or into, the hegemonic grid and--peers back. According to John Berger, such a moment of recognition is rare today, a time when animals have become so objectified through our will to knowledge that we no longer see them looking back, or we encounter their gazes in "safe, sanitized" settings (Armbruster 227), such as museums, documentaries--and bird guides. Homi Bhabha's poststructuralist analysis of the colonial subject's psychological dilemma seems just as à propos here: "in the identification of the Imaginary relation there is always the alienating other (or mirror) which crucially returns its image to the subject; and in that form of substitution and fixation that is fetishism there is always the trace of loss, absence" (81). The human ego's tenuous negotiation of desire and fear, identification and difference, is here disrupted by the owl's own "re-inscription," as it were, of its very representation, an uncanny eruption of the "Other" into consciousness.

Peterson's visual "commitment" extends to his text, a "terse" one that "rarely included descriptions of song or behavior," concentrating rather on "information about size and appearance" (Gibbon and Strom 298). Here Peterson seems due for applause in his lack of Romantic effulgence common to previous presentations of this ilk. (His shortest entry, for example, describes the Robin in a matter-of-fact laconism: "The one bird that everybody knows" [107]!) Aside from visual descriptions of individual species, Peterson has brief introductory sections to certain ornithological families and a few "important" sub-families and genuses, as if balancing a drive towards taxonomical order with his audience's need to get its identification skills up to snuff. But taxonomy is still underscored in the book's evolutionary sequence, with the most "primitive" birds first, the most "evolved" last.

His lack of attention to bird songs (and behavior) is, I would contend, another unconscious effort to remove "life" from the bird. Peterson's rationale is, again, ostensibly laudable: "Song description," with a few exceptions, "is dispensed with" as an absurd anthropomorphism, evidenced in the ridiculous "syllabifications" of previous attempts at aural description (xix).{9} But at last, the bird is a now a creature of no sound, no color, no life: a mere object of specularity placed in its taxonomically determined place on the page, so that the birder can say, "I know you." (And I appropriate you in my colonizing, will-to-knowledge act of "ownership.")

Indeed, Peterson's hobbyist emphasis on birding as a "most absorbing game," as a "most fascinating diversion" (xviii) conceals the Nietzschean will to knowledge and power entailed in this mere "hobby." The birder in fact achieves a certain sense of ontological and epistemological security, I would argue, in the very act of identification, of "knowing": he/she is initially "puzzled" by an (oh, no!) unknown bird; but, empowered by the wonders of Peterson's scientific method, the birder can soon "feel confident" (xvii) in assigning that particular Other in a comfortable categorical niche within the cognitive universe of the imperial Self.

That Self feels most disturbed in the presence of "rare" species, which are both privileged as novelty objects in the "game" and regarded as sources of anxiety: thus such "accidentals and rarities" take up a good deal of Peterson's introduction, as if their occasional incursions into the "territory he [the birder] knows so thoroughly" (xviii) were intrusions of the Other that needed to be "conquered" via the act of identification, a reduction to Sameness and Self. The fact that they are also privileged for their rarity might be best explained by Berger's and Wilson's related notions that such an interest in rare species is spurred by modern humankind's perceived loss or lack, in the wake of a "progressively waning contact" with nature (Armbruster 226; cf. Lacan, bien sûr). Americans, especially, seem to combine a manic drive for technological progress with a melancholy longing for "Mother Nature on the run."{10} But such ego-recuperative feelings (if I may lower my argument to the level of pathos) have not been enough to prevent the extinction of the Dusky Seaside Sparrow [plate 6 (text)], whose description in the Guide would read like an obituary, if only the "is" of Peterson's text were changed to a "was."

Indeed, Peterson's advice in his introduction demonstrates a certain disregard for actual birds, given its accent on naming, on sheer identification. Via the field marks culled from pictures and text, the birdwatcher can often identify a species by "elimination": thus one particular eye-stripe or breast-spot "eliminates" other species from consideration; and again, by narrowing the possibility of three species down to one, the "student . . . ceases bothering[!] about the other two" (xx). (Of course, the birder can now cease bothering completely about the Dusky Seaside Sparrow.)

A final crack in the naturalist edifice shows through in the last paragraph of Peterson's introduction, as he congratulates himself for the humaneness of his enterprise. While previous ornithologists "seldom accepted a sight record unless it was made along the barrel of a shotgun[!]," now we only need binoculars and the ability to "trust our eyes" (xxi). Yes, we are no longer gunning down odd-colored birds, to carry them off to the "bird guy" who lives down the road; but we are still wielding the "gun" of our colonial gaze (a gun with a high-powered scope, to be sure), bringing order to our own world-view and psyches, as the non-human Other is finally rendered an object of our desire for "categorical" completion.

III. Peterson's Guide vis-á-vis Class, Gender, & Race

III. Peterson's Guide vis-á-vis Class, Gender, & Race

"In most American nature writing," nature "is constructed" as an "unmarked body" that is "raceless (white), genderless (male), sexless (heterosexual), and classless (middle class)" (Legler 72). Or better, it is Peterson's "I," his ornithological lens, that projects such qualities upon his subject matter (Pratt 31), and yet mystifies or occludes such projections through a stance of scientific objectivity, or pure hobbyist fun. Behind the Guide, then, the alterities of race, class, and gender lie submerged, and the birds on its pages are thus (and also) displacements for the human abject, demonstrating that such "narratives of nature" cannot be separated from the "political and cultural agendas" that they "implicitly promote" (Philip 301).

As for economic class, Peterson's project assumes the leisure for such a class-privileged "game" (and the economic wherewithal to afford binoculars, bird guides, field trips, etc.). Such naturalist pastimes are, au fond, a Romantic "view of nature . . . that . . . depends on individual feeling, on consciousness, on the leisure to enjoy sunsets and spring days" (Bate, Romantic 53), an attitude towards nature, at last, "only available to the highly 'cultured'" (Philip 304). If the Guide were indeed "packaged by Peterson to be played by all comers" (Gibbon and Strom 300), his democratic gesture was a failure: rather, it appears that Peterson's oft-invoked "student" is actually a code-word for--the privileged. One might even question here Peterson's exclusion of the Western U.S. in his limiting of the Guide's scope to "Eastern Northern America." In the 1930's, the WASP leisure-class "birding" class was still centered on the East Coast, and so Peterson's guide to Western birds (a false geographical schism in itself) would have to wait a few more years.

Nor should we forget that Peterson's Guide requires the literacy to navigate through a text filled with latinate names for avian body parts and other "heavy" ornithological apparati. Such literacy is part of the "Imperial Eye," which is, as Pratt tells us, not only "European" and "male," but also "lettered" (31). As for Pratt's "European" angle, the bird names in the Guide--most formulated long before Peterson, of course--often bear the burden of English nostalgia for home. That is, many native American birds have been given English names that may have little bearing to "scientific" taxonomy: thus the "original" European Robin has been provided a namesake in the New World--the American Robin, related more to the Song Thrush and (European) Blackbird than to its nominal Euro-"twin." Bird by bird, the New World species have been Europeanized, often by simply having "American" prefixed to a European name; and taxonomically new, independent families of birds have been appropriated via the simple prefix "New World"--e.g., "New World Warblers." (Admittedly, this latter practice is even more common in recent guides, following changes in the official scientific taxonomy.)

The presence in the Guide of such European-introduced imports as the Starling and House Sparrow, too, denotes a similar yearning for the "same old place."{11} Ironically (and yet appropriately, as a case of colonial parallelism), the "colonizing" propensities of the two European birds mentioned have resulted in the displacement of many native species of songbirds--and the lamentable (to the birder, at least) ubiquitous domination of these two imports in many U.S. towns and cities. At last, the "Euro-American" birder is privileged enough to be able to use Peterson's Guide to identify various avian denizens of the New World; but even this identification of the "new" often implies a desire for the "old," a desire whose residues are thus still evident in the "proselytizing" handbooks that are the legacy of 19th-century natural science.

The critique of imperialist sexism in such texts would begin with an obligatory noting of the "feminization" of the Other; and indeed, a Lacanian metonymical analysis of the avian Other as Nature<->Female(<->Mother) could easily be essayed.{12} But what is most striking about Peterson's "male gaze" is his blatant foregrounding of the male. Whenever there is enough sexual difference in plumage (feather coloring) to require the illustration of both male and female birds, the usually more brightly feathered male is inevitably presented in front of the female of the species [plates 1-2, 5]. To the common-sense objection that the males' more visually "spectacular" nature in such sexual bifurcations justifies such a focus--a culturally biased, "scopic" judgment itself, no doubt--I would point to the plates of the birds of prey (that is, hawks and owls) [plates 3-4]. In these cases, only one, unisexual, illustration is offered for each species: but nowhere in the plates or text is it acknowledged that, in such species, the female is (usually) the larger, more dominant, bird. In sum, "superior" males are privileged, but "superior" females are ignored; and the "inferior" females are kept in their proper place, as the "background," insignificant-other half of the illustrated pairs.

In terms of "race," I have already mentioned in a previous section the analogue between imperialist human ethnological hierarchies and the evolutionary-ordering taxonomy of ornithology. In general, from Linnaeus's 18th-century taxonomical system to 20th-century museums, Western classifications of nature have been a method of naturalizing "specific class, race and gender organizations" (Legler 74).{13} If we accept the nature-to-human historical progression of taxonomy for a moment, it's a small (and no doubt self-justifying) step from valuing relatively evolutionarily "advanced" songbirds over more "primitive" waterfowl to valuing one (colonizing) human "race" over other human "races." (I noted above that "race" is a longtime synonym for "sub-species" in biology: what a novel and perhaps unsettling notion it would be to introduce the term "sub-species" into human political debates over the various "races" of humankind!) Thus birds (and animals in general) are not only sites for projection of the feminine Other noted above, but for the "inferior" racial other, as Nature itself continues to be "the site on to which constructions of the 'primitive' are projected" (Philip 303). In sum, birds and nature can be read, on one level, as surrogate, metonymic displacements of the anxiety-ridden modalities of race, class, and gender: but they are also more than that. I would contend that Nature itself, at last, is another site of "recognition and disavowal," to use Bhabha's terms, through which the human subject achieves that "ideal ego that is white and whole" (76).

Indeed, moving away from human socio-politics, one might view the naturalist project in general as one in which Nature becomes the ultimately alienated and reified Orientalist Imaginary. To return to the real "objects" of Peterson's Guide, I would insist again that it is the avian Other, above all, who has here been "colonized" by Pratt's "Imperial Eye"--or Roger Tory Peterson's "Colonizing Binoculars"--and I would suggest at last that the concerns of colonial discourse theory and eco- or "green" criticism might thus be acknowledged as close relatives with kindred goals. It may well be that the counter-discursive "holy trinity" of race, class, and gender/sexuality is missing its Jungian "fourth," or inferior function{14}: that of species, or the organic and non-organic non-human in general. (But even this last distinction between organic and non-organic is a Western binary called into question by various submerged non-Western and New Age archaeologies of knowledge.) The possibility of such a holistic re-"vision" of alterity theory will serve as this essay's coda.

IV. Conclusion: Towards A Green Anti-Colonialism

IV. Conclusion: Towards A Green Anti-Colonialism

In his latest plea for the New World "Caliban," for the neocolonial "South" against the imperialist "North," Retamar makes ecological concerns an integral part of his lament, noting that "innumerable animal species have already been extinguished by the human animal, especially [and of course] in its Western or Northern variety": therefore his call for a "Green" or eco-consciousness to be incorporated into the global war of haves and have-nots (169). This environmental concern has been voiced intermittently by many postcolonial theorists (especially those with transnational assumptions), no matter how heated their particular human ideological battles.{15} However, as noted above, Nature has usually remained the denigrated "fourth" in such political studies of the colonial agenda.

Jonathan Bate's 1991 Romantic Ecology attempted to change the critical milieu, as a self-proclaimed "preliminary sketch towards a literary ecocriticism" (11). In an attempt to redraw the "political map" of literary criticism (4), he asks us to reconsider whether the "economy of human society is more important than . . . the economy of nature" (9). Such a provocation no doubt flew in the face of British liberal-Marxist tradition, with its longtime emphasis on class issues.{16} Indeed, Bate seems to go out his way to assert, almost defensively, that an environmentalist focus "need not be the dupe of conservative politics" (114). But the 19th-century proto-environmentalists whom Bate champions were hardly peasants or factory workers, making Bate an easy target for a Marxist backlash. However, my problem with Bate's "revolution" is that, at bottom, his rationale for re-privileging the environment is above all a very selfish, human one: implicit in his entire eco-harangue is the fear that, "if the planet perishes, so do we poor stupid humans!" And so I've introduced Bate here to acknowledge that a blind rush towards the "ecocritical" label is hardly a satisfactory resolution to acknowledging the non-human Other.

For one thing, no one is even sure what "ecocriticism" is yet: it could be writing about nature-writing, or exploring the "themes and uses" of Nature in literature, or--more usually--critiquing literature from a quite political stance, as Marxists and feminists have done.{17} However, the political concerns of an ecocritical environmentalism (like those of postcolonial nationalism) are immediately greeted by the onslaught of poststructuralism. For instance, Mazel, employing Foucault, wonders "whether the construction of the environment is itself an exercise of cultural power." Indeed, not only is the environment itself a "construct," but environmentalism, too, is perhaps a form of Orientalism (142-144). (To deem the "Earth" in "Save the Earth" as a constructed false essentialism strikes the right brain as rubbish--but the left brain finds any rebuttal difficult.) Regarding environmentalism's Orientalizing nature, Dominic Head also notes "a perceived drive towards fundamentalism in deep ecology" (27)--witness the fanaticism of certain radical environmental groups--and Kerridge warns that environmentalism might become another well-meaning but ultimately fascist colonialism.{18} At last, any cogent ecocritical stance must also include a critique of the implicit ideologies of environmentalism itself.

Another major problem for ecocriticism is the question, "Can Nature Speak?"--or "Who Will Speak for Nature?" My guiding rationale for reading Peterson's Guide as an act of colonization has been an attempt to extend Said's call for "articulating those voices dominated, displaced, or silenced by the textuality of texts" (1222). Said has in mind the human colonized, of course; but the avian "voices" of the naturalist's "museum" are perhaps even more "dominated," "displaced," and "silenced." However, any attempt to incorporate the non-human Other into something close to human alterity theory becomes immediately problematic if one broaches the ubiquitous postcolonial theme of the Other's potential, or need, for resistance. Obviously (assuming that discourse = human language), discursive "counter-narratives" of resistance on the part of birds themselves is a ridiculous notion, unless one invokes some nightmare from Alfred Hitchcock--although the notion of a trans-species, trans-semiotic "discursivity" remains an intriguing thought. We return, then, to environmentalists or ecocritics who, again, must provide a surrogate defense, like 3rd-World academics attempting to "speak for" the subaltern. Karla Armbruster offers a precedent, at least, in noting that "humans who speak for" the "non-human" Other are similar to feminist critics, etc., in that they are at least "part of a larger group"--in this case, Nature itself (220).{19} And, as Head's skeptical discussion of ecocriticism admits, "postcolonialism and ecologism" are really kindred "branches of postmodernism," in that both "adopt a position of informed decentring" (29). As I have suggested, after the decentering of (human) race, class, and gender, ecocriticism's decentering of the "human" itself as the sole viable site of alterity is the next logical step in a general theory of Otherness.

My last and greatest hesitation in making a "leap" to the non-human Other is the seeming impossibility of doing so, given again the poststructuralist decimation of the subject's ability to truly "know." In the Lacanian view, for instance, human consciousness is so inextricably bound within language, within the Law of the Father, that to somehow reach a "Real" Other that is not some mere slippery-signifier-metonym-displacement for the Imaginary Other (at last, the Mother) seems an epistemological impossibility. The "Real"--including the "real" bird, etc.--is beyond representation (and therefore knowledge), according to Zizek's version of Lacan. But Zizek's rather Bhabha-esque take on the "Real" offers a ray a hope: the Real is a "non-symbolic kernel that makes a sudden appearance in the symbolic order, in the form of traumatic 'returns' and 'answers'" (qtd. in Kerridge, "Introduction" 3). Maybe the Great Horned Owl that surprised me when I was a boy, flying as it did, silent, a few feet over my head, disappearing immediately into the next stand of pines, was once such "trauma" of the Real. And maybe that's how the non-human Other "speaks." And asks humans to "speak for" it. (I realize that such an experiential response would be viewed by the poststructuralist as a red-herring attempt to emotionally elicit a "truth" that is at last fraught with "gaps.")

I have apparently wandered far from Peterson's Guide. Returning to my ostensible subject matter, I certainly am not condemning Peterson's agenda for any conscious complicity in some Euro-American conspiracy of Othering. Ironically, such apparently ecopolitically correct organizations like the Audubon Society continue to publish guides based largely on Peterson's system, on his "way of knowing" and his means of appropriating avian alterity. But besides trying to bring the rather inchoate agendas of colonial discourse theory and ecocriticism into closer proximity, I have tried to show that even such "enlightened" ventures towards an appreciation of the natural world are necessarily collaborative with a Western colonizing discourse of power that has crucial ramifications not only for the Others of race, class, and gender, but for the spec-ial Other. The fact that this last Other has no(?) discursive recourse to resistant counter-narratives renders its plight all the more tragic to whatever notions of conscience and justice are left to the postmodern psyche.

When the last Dusky Seaside Sparrow sang its final song to its last spring a few years back, the "aporia" went relatively unnoted by academics writing learned treatises on "imagined communities" and "strategic essentialism"--still towing, really, the same Euro-homocentric line that they've condemned for years. When the last homo sapiens dies because our own species' "will to knowledge" could never transcend such a worldview, could never transcend our own antagonistic, Manichean approach to the ecosystem of the planet, all debates about "the third stage of the subaltern's progression towards nationalism" will be--well, over.

1

"Peterson's great achievement immediately overshadowed earlier field

guides. The authority of his comprehensive visual system has sometimes been

challenged but never undercut" (Gibbons and Strom 295).

2

See Pratt's Imperial Eyes, especially 24-37; for the American landscape in particular,

see Linda Bolton's reading of Jefferson's specular "othering" of the Virginia landscape.

3

Whether the taxonomy of "natural history" was subsequently transferred to human

"races" (creating, among other ideologies, that of racial Darwinism) or was

actually the displaced methodology of a hierarchal ("Great Chain of Being"),

analytical, and already "racial" world-view is perhaps a chicken-egg dilemma

that I have neither the time or need to answer here. Linnaeus' own

categorization of humans came later in his project (Pratt 32). Chatterjee, too,

in a move ostensibly surprising for a colonial discourse theorist, privileges

the "man-nature" binary: the "knowledge of Self and . . . Other" implicit in the

relationship "between man and nature" was subsequently "transferred" to

"relations between man and man" (14). Conversely, Bookchin contends that the

"domination of nature by man stems from the very real domination of human by

human" (qtd. in Killingsworth and Palmer 196); and Philip prefers to read Nature

as the site where issues of human "race, gender, and property relations" are

played out (303; see also Legler 74).

4

The all-encompassing goal of such classification, according to Pratt, was to

locate "every species on the planet, extracting it from its particular,

arbitrary surroundings . . . and placing it in its appropriate spot in the

system (the order--book, collection, or garden) with its new written, secular

European name" (31). Tellingly, the "systematicization of nature coincides with

the height of the slave trade, the plantation system, [and] colonial genocide in

North America and South Africa"--indeed, all are similar "massive experiments"

in "discipline . . . and standardization" (36).

5

I don't claim that evolution isn't itself a diachronic process , only that the

"species" relationships that ornithologists have puzzled over for scores of

years haven't changed significantly in thousands of years. The ornithologist

might object that these revisions are simply hypothesis adjustments, part and

parcel of the scientific method--and yet I would maintain that they remain

symptoms of an anxious drive towards control that inevitably contradicts itself.

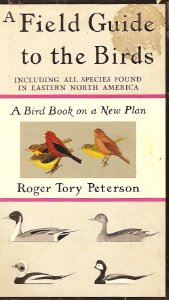

6 The "appended plates" refer to xeroxes from Peterson included with the original hard-copy essay. Without permission to scan pages from the Guide for Web presentation, I can only direct the reader to relevant page numbers (okay, so I scanned the cover):

--Plate 1: front cover (dust cover of "commemorative" ed.)

--Cover graphic:

--Plate 2: pp. 26-27

--Plate 3: pp. 38-39

--Plate 4: pp. 88-89

--Plate 5: color plate between pp. 136-137

--Plate 6: pp. 146-147

As for the general "museum" layout immediately alluded to,

one can simply open the book at random to nearly any page.

7

Bird guides to this day follow Peterson's visual layout, for the most part.

Perhaps the most important revision of Peterson's mode of presentation has

simply been to keep the text and pictures of each species on the same set

of facing pages, an even better ordering, at last.

8

Peterson does impart at least one "humanizing" touch in his plates: the almost

calligraphic hand-lettering of names and descriptions [see plates 2-6].

9

Examples: in the older guides, the Robin supposedly sings, "Cheer up!

Cheerily!"; the White-Throated Sparrow whistles, "Old Sam

Peabody-Peabody-Peabody"; and the Whip-Poor-Will (oh, poor Will!) tells everyone

its name, of course.

But even Peterson sometimes reverts to such anthropomorphic descriptions. Lyon's

categorization[!] of nature writing places field guides (with Peterson as prime

example) at the most "objective" of the spectrum of nature writing; and yet he

notes Peterson's own "literary" description of the "gushing" song of the Canyon

Wren (274, 276).

10

Thus Bate quotes de Tocqueville on this mixed-feeling" relation to the

American landscape: "It is this consciousness of destruction . . .

that gives . . . such a touching beauty to the solitudes of America.

One sees them with a melancholy pleasure. . . . Thoughts of the

savage, natural grandeur that is going to come to an end, become mingled with

splendid anticipations of the triumphant march of civilization" (qtd. in

Romantic 39). Oddly, Bate seems to consider this a rather positive

proto-ecological stance.

11

Both species were intentionally introduced by "homesick" Euro-Americans:

symptomatically, the Starling's arrival was part of a project to "introduce into

America all the birds mentioned by Shakespeare" (Gibbon and Strom 216)!

12

I have attempted as much in a previous semi-Lacanian study of Wordsworth's bird imagery.

13

Outside the scope of my immediate concerns here is Legler's discussion of the

"body" of both human and animal: body politics itself is "the politics of naming

and exerting control over both non-human and human bodies" (73).

14

I use the Jungian idea as a metaphor only. Jung used his observation of an

"archetypal" impulse of the "three to the four"--a drive towards wholeness, in

his view--to critique the Catholic trinity as in need of its repressed "fourth"

(alternately, "Satan" [Shadow] or a female [Anima] deity) and to explain his

concept of individuation as, in part, the task of making conscious the fourth,

repressed function (be it thinking, feeling, sensation, or intuition) in his

theory of personality.

15

Thus Stuart Hall speaks of an "ecological consciousness that has to have, as its

subject, a base larger than the free-born Englishman" (177), and Chatterjee

notes in passing the Indian peasants' belief in a "bioregionalism" that

transcends national borders (146; see also Bate, "Poetry 59). In more concerted

fashion, Kativa Philip's recent essay ("English Mud") offers an interesting

reading of the "environmental politics" (304) involved in the British colonization of

India.

16

In developing his specific argument--Wordsworth as precursor of modern English

environmentalism, through such "eco-socialists" as Ruskin--he boldly claims that

English socialism, since the Romantics, has always been more "green" than "red"

(Romantic 33, 58).

17

See, for instance, Glotfelty xviii-xx, and the sheer range of the essays in the

two ecocritical collections in my Works Cited by Glotfelty & Fromm and Kerridge

& Sammells. [Having written this sentence about two years ago, I do perceive a

greater self-assured "codification" in the "ecocriticism" of 2000-2001.]

18

"Introduction" 7; see also Campbell 30; Bate, "Poetry" 59.

19

Kerridge, via Kristeva, poses a problem for the whole project of speaking for

the eco-other: since there is no "outside" to the "global ecosystem," is there

any Kristevan "abject" to speak for ("Small Rooms" 190)?

[--To the Top--]

Armbruster, Karla. "Creating the World We Must Save: The Paradox of Television Nature

Documentaries." Kerridge and Sammells 218-238.

Bate, Jonathan. "Poetry and Biodiversity." Kerridge and Sammells 53-70.

---. Romantic Ecology: Wordsworth and the Environmental Tradition

. London: Routledge,

1991.

Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1984.

Bolton, Linda. "The Discourse of Freedom in the Absence of Ethics: Thomas Jefferson and

the American Mind." Unpublished essay, 1998. [In Ethical Disruptions and the American

Mind. Forthcoming in the series, "Horizons in Theory & American Culture," LSU Press.]

Chatterjee, Partha. Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World: A Derivative Discourse?

Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press, 1986.

Gaull, Marilyn. English Romanticism: The Human Context. New York: Norton, 1988.

Gibbons, Felton, and Deborah Strom. Neighbors to the Birds: A History of Birdwatching in

America. New York: W.W. Norton, 1988.

Glotfelty, Cheryll. "Introduction." Glotfelty and Fromm xv-xxxvii.

---, and Harold Fromm, eds. The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology.

Athens: U of Georgia P, 1996.

Hall, Stuart. "The Local and the Global: Globalization and Ethnicity." McClintock, Mufti,

and Shohat 173-187.

Head, Dominic. "The (Im)possibility of Ecocriticism." Kerridge and Sammells 27-39.

Kerridge, Richard. "Introduction." Kerridge and Sammells 1-9.

---. "Small Rooms and the Ecosystem: Environmentalism and DeLillo's White Noise."

Kerridge and Sammells 182-195.

---, and Neil Sammells, eds. Writing the Environment. London: Zed Books, 1998.

Killingsworth, M. Jimmie, and Jacqueline S. Palmer. "Ecopolitics and the Literature of the

Borderlands: The Frontiers of Environmental Justice in Latina and Native American

Writing." Kerridge and Sammells 196-207.

Legler, Gretchen. "Body Politics in American Nature Writing: 'Who May Contest for What

the Body of Nature Will Be?'" Kerridge and Sammells 71-87.

Lyon, Thomas J. "A Taxonomy of Nature Writing." Glotfelty and Fromm 276-281.

Mazel, David. "American Literary Environmentalism as Domestic Orientalism." Glotfelty

and Fromm 137-146.

McClintock, Anne, Aamir Mufti, and Ella Shohat, eds. Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation

and Postcolonial Perspectives. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Peterson, Roger Tory. A Field Guide to the Birds: Giving Field Marks of All Species Found

in Eastern North America. Illustr. Roger Tory Peterson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin,

1934.

Philip, Kavita. "English Mud: Towards a Critical Cultural Studies of Colonial Science."

Cultural Studies 12 (1998): 300-331.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge,

1992.

Retamar, Roberto Fernández. "Caliban Speaks Five Hundred Years Later." McClintock,

Mufti, and Shohat 163-172.

Said, Edward W. "The World, the Text, and the Critic." Critical Theory Since 1965. Ed.

Hazard Adams and Leroy Searle. Tallahassee: Florida State UP, 1986. 1211-1222.

Williams, Patrick, and Laura Chrisman. "Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory:

An Introduction." Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader. New York:

Columbia UP, 1994. 1-20.

And thanks to environment.miningco.com for the Great Horned Owl graphic.

[--To the Top--]

First Created: 8/15/01

Last Revised: 4/16/07