| |  |  IMMEDIATE ASSIGNMENTS: IMMEDIATE ASSIGNMENTS:• For TH, 3/24: Indians in Unexpected Places: "Athletics" (109-135)

—ALL students: mark 2-3 "significant" passages

—"selected students" (T-W): Response #4; uploaded to Canvas by W, March 23rd, by midnight • Reminder: Quizzes will always/only involve the readings assigned for that day. •

(Moreover, the make-up is a lot more work—for both of us!• For TU, 3/29: Indians in Unexpected Places: 136-223

—ALL students: mark 2-3 "significant" passages for each assigned chapter;

—"selected students" (E-K, L-Ph): Response #4; uploaded to Canvas by M, March 28th, by midnight • For TH, 3/31: Indians in Unexpected Places: 224-240 (Conclusion)

—ALL students: mark 2-3 "significant" passages

| Extra Credit Opportunity: Write a one-page-or more summary of/response to this lecture, for a max of 10 extra credit points (due as email attachment by SU, April 20th, midnight). Note that register to attend the webinar:::: | -=- The E.N. THOMPSON FORUM ON WORLD ISSUES -=-

Walter Echo-Hawk: "Reckoning and Reconciliation on the Great Plains": April 6, 7:00 p.m., Lied Center for Performing Arts"Echo-Hawk is an author, attorney, and well-renowned legal scholar. Echo-Hawk's wealth of experience and knowledge will inform Nebraskans not only about the histories of injustice against Pawnee people and other Indian nations, but also about how we can all take steps to heal from and repair the abuses of the past to build a society based on dignity and respect for all. Walter Echo-Hawk will share his deep knowledge of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and truth and reconciliation efforts to bring justice and healing to Indigenous peoples in Nebraska, and worldwide. For more information, to reserve free tickets, to watch the livestream, or to access recorded lectures, visit https://enthompson.unl.edu." [My note:] Echo-Hawk's role in recent Native activist legislation is seminal:

• "As a staff attorney of the Native American Rights Fund (1973-2009), he represented Indian Tribes, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians on significant legal issues in the modern era of federal Indian law, during the rise of modern Indian Nations in the tribal sovereignty movement. He litigated indigenous rights pertaining to religious freedom, prisoner rights, water rights, treaty rights, and reburial/repatriation rights."

• "1986-1990: He represented tribal clients to obtain repatriation legislation: (a) precedent-setting legislation in Nebraska (1989) and Kansas (1988) directing museums to return and rebury dead bodies and grave objects to Tribes of origin; (b) the 1989 reburial agreement with the Smithsonian Institution enacted into the National Museum of the American Indian Act; (c) the 1986-1990 legislative campaign culminating in the passage of Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA)."

• "1990-1994: He represented the Native American Church of North America to obtain passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act Amendments of 1994.

• "In 2010, he represented the Klamath Tribes in a trial to quantify treaty-protected Indian water rights for hunting, fishing, and gathering purposes; and various Tlingit tribes to repatriate sacred objects and cultural patrimony." |

The 1491s: "I'm an Indian, Too" (YouTube) The 1491s: "I'm an Indian, Too" (YouTube) |

|---|

| —The 1491s are a Native comedy troupe, and in case it's not obvious, this vid is, in part, another satire on "Pretendians" and Indian wanna-be's. But more generally, it's "theme" is—"Hey, there are all kinds of Indians"?! (Oh, I just found out that this is a satire of an old show tune!—see next.) |

|

|---|

|

|---|

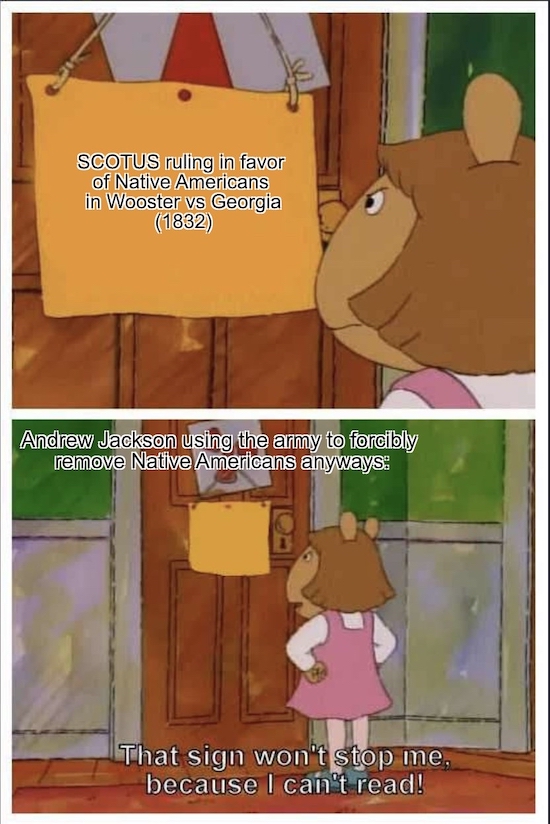

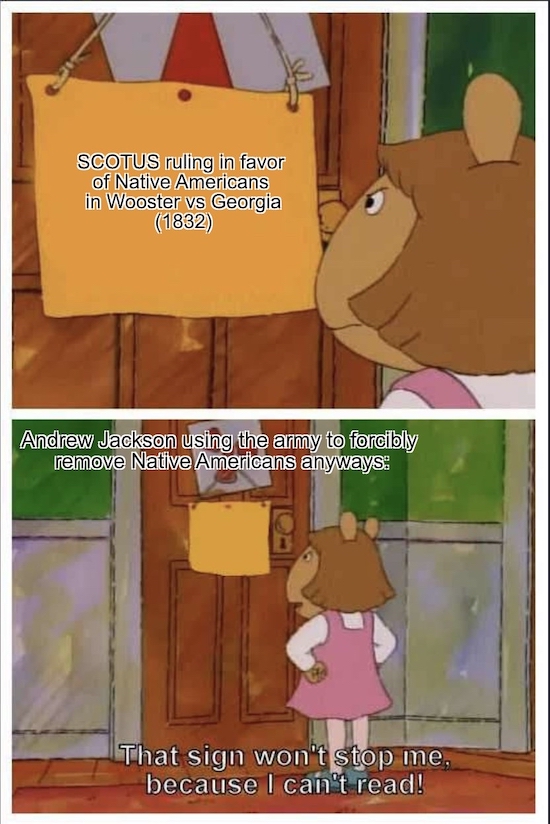

| —Meme just shared w/ me by a student (thanks!); if you don't get it, see K&V 64-65. (Of course, "Wooster" should be "Worcester.") |

|

|---|

|

|---|

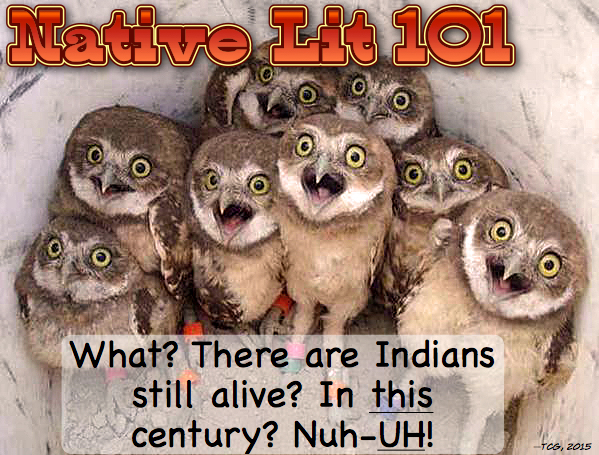

| One might say that P. Deloria's entire book is "simply" about proving this stereotype false. |

|

|---|

|

|---|

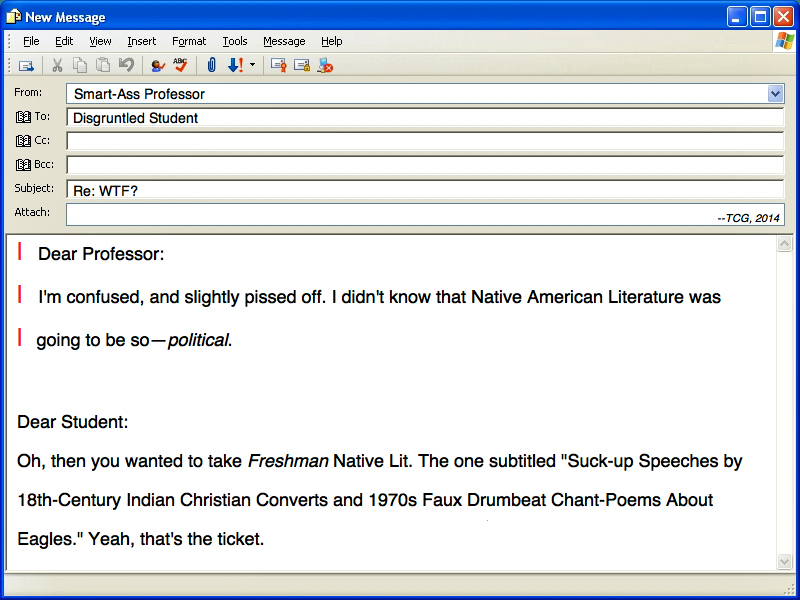

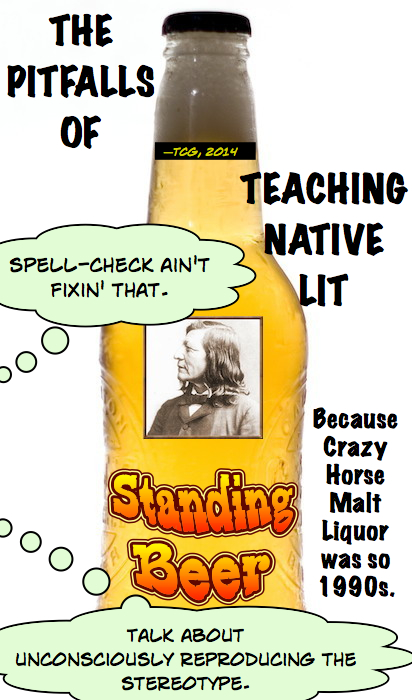

| —a common reaction to my Native Lit courses |

|

|---|

|

|---|

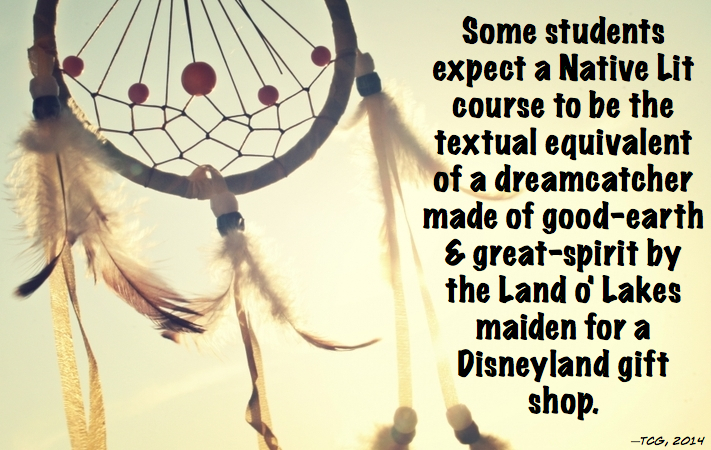

| —another common reaction to my Native Lit courses |

|

NOTE: I am intentionally brief, even abbreviatory, in the following NOTES because I mean them to function as reminders & sources of review rather than to serve in lieu of coming to class: they DON'T. However, this page has a further usefulness: by "Commentary," I mean that some points in these class notes are expanded upon (and re-organized) in ways that our limited class time—and my rather manic teaching style—disallowed. . . .

| = = = = PRESENTATION GROUPS = = = = |

|---|

• I have created RANDOM groups for the final class presentations via Canvas's randomize function. (In Canvas, go to "People"=>"Presentation Groups." You can also email the rest of your group, if need be, via Canvas's Inbox.)

• I will adjust these groups only to address inequities in group sizes due to student drops or chronic truancies.

• Don't worry, Group #1, we'll draw lots to see who goes first! | | | #1: Andrew Brandt, Nicholas Burbach, Karley Coday, Laekyn Collins, Jonathan Harrah | | | #2: Violet Hudson, Isabelle Kripps, Shay Parlier, Wakinyan Running Bear Strecker, Caitlyn Thomas | | | #3: Alexie Logue, Jacob Newburn, Helen Philbrick, Bella Syslo | | | #4: Breanna Armstrong, Kalli Kilgore, Faithleigh Podzimek, Susie Welker | | | #5: Evelyn English, Viangri Sontay Lopez, Rianna Wells, Brittney White |

TU, Jan. 18th:: Syllabus, etc.; incl. my Native American History "Outline" (PDF, in the "00 Intro Materials" folder on Canvas) TU, Jan. 18th:: Syllabus, etc.; incl. my Native American History "Outline" (PDF, in the "00 Intro Materials" folder on Canvas)

TH, Jan. 20th:: Healy's "American Indians" chapter (my PDF summary in the "00 Intro Materials" folder on Canvas); Burns poem: TH, Jan. 20th:: Healy's "American Indians" chapter (my PDF summary in the "00 Intro Materials" folder on Canvas); Burns poem:

SURE YOU CAN ASK ME A PERSONAL QUESTION How do you do?

No, I am not Chinese.

No, not Spanish.

No, I am American Indi—Native American.

No, not from India.

No, not Apache.

No, not Navajo.

No, not Sioux.

No, we are not extinct.

Yes, Indin.

Oh?

So that's where you got those high cheekbones.

Your great grandmother, huh?

An Indian Princess, huh?

Hair down to there?

Let me guess. Cherokee?

Oh, so you've had an Indian friend?

That close?

Oh, so you've had an Indian lover?

That tight?

Oh, so you've had an Indian servant?

That much?

Yeah, it was awful what you guys did to us.

It's real decent of you to apologize.

No, I don't know where you can get peyote.

No, I don't know where you can get Navajo rugs real cheap.

No, I didn't make this. I bought it at Bloomingdales.

Thank you. I like your hair too.

I don't know if anyone knows whether or not Cher is really Indian.

No, I didn't make it rain tonight.

Yeah. Uh-huh. Spirituality.

Uh-huh. Yeah. Spirituality. Uh-huh. Mother

Earth. Yeah. Uh-huh. Uh-huh. Spirituality.

No, I didn't major in archery.

Yeah, a lot of us drink too much.

Some of us can't drink enough.

This ain't no stoic look.

This is my face. —Diane Burns, c. 1989 |

' * VINE DELORIA, JR.: "Indian Humor" (Trout 654-62)  |

|---|

| | * humor => a people's "collective psyche" (655) | | | | —NatAmer. the "opposite," really, of the "wooden Indian"/"Kawliga" stereotype (655); key reason for humor?: survival! (662) | | | * JOKES: Columbus; Custer; Christian missionaries; nationalism, and . . . | | | | —"militancy" (656, 660-662): note date of essay (1969); indeed, Deloria's sometimes strident tone of protest approaches that of the A.I.M. (the American Indian Movement) of the late 1960's & early 70's. . . . |

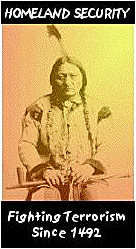

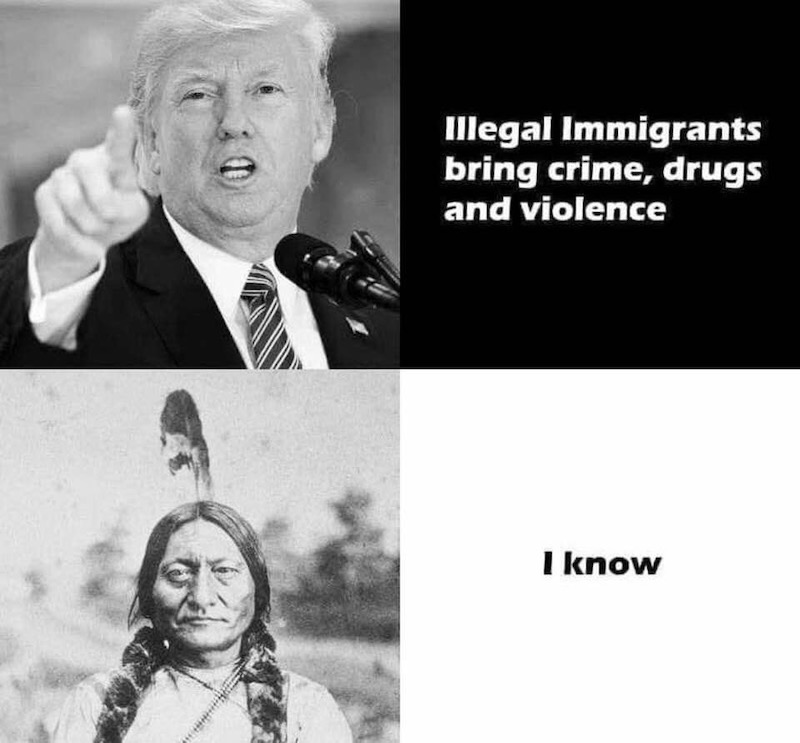

| | À propos of Native "militancy,"

here is my version of the

popular bumper-sticker/t-shirt

slogan (replacing an armed

Geronimo & company with

Tatanka Iyotanka [Sitting Bull]) |  |

| • Vis-à-vis Vine Deloria, Jr. on Custer: |  |  |

|---|

| (painting by William Reusswig; jokes stolen from Vine Deloria, Jr.) | (graphic "borrowed" from Google Images) |

|

|---|

Regarding Deloria's joke about Custer being a

"well-dressed" fellow at the Little Big Horn—

a photo of the neck tag of my

almost brand new ARROW shirt |

TU, Jan. 25th:: TU, Jan. 25th::

* Vine Deloria, Jr.: "Indians Today, The Real and Unreal" (Trout 7-15) * Vine Deloria, Jr.: "Indians Today, The Real and Unreal" (Trout 7-15) |

|---|

| | * "Indians," above all, PROJECTIONS of a Western colonial MYTHOLOGY, "mythical Indians of stereotype-land" (7-8) | | | | —early colonial myths from Columbus, on—often of a (positive) "noble savage" (8-9, 10) | | | | —but also incl. negative conflation with other animals, as (a wild/non-human) "savage" and a "wild species" (9-11, 12) | | | * Indeed, whites (often claim to) "understand Indians"—largely based on pop. stereotypes, however (10). | | | * White Americans' NEED to IDENTIFY with/as Native American (8-9)—Why?: | | | | —"Indian-grandmother"/"descendent of Pocahontas" complex: female (less threatening), a New World "royalty" (9) | | | | —need for "some blood tie with the frontier," with the American soil? (9) | | | | —an avoidance of "facing the guilt" of white culture's abusive treatment of Native Americans? (9) | | | * Legal/social status, contrasted with historical plight of African-Americans (11-13) | | | | —Natives not "recognized" as human until the colonizers' realization: "they got land!" (11) | | | | —African-Americans traditionally segregated [as the OTHER], NatAmer assimilated [as the SAME] (12) | | | * NatAmer vs. Western WORLDVIEW [fairly essentialist] (13) | | | —NatAmer "simplicity and mystery" vs. Western "knowledge"?! (13) (Elsewhere, Deloria says, "The white man . . . has ideas; Indians have visions." As for Western religion: "The Christian environment is always a ruined and destroyed, a totally exploited, environment.") | | | | | | | —NatAmer pre-Columbian political history also laudable in its democratic structure (13) | | | * Final CALL TO ACTION: "What we need is a cultural leave-us-alone agreement" (14). (Any problems with this assertion?) |

"Take a Picture with a Real Indian" (James Luna [YouTube]) "Take a Picture with a Real Indian" (James Luna [YouTube]) |

|---|

—Related to Deloria's point that most Americans only "know" (and want) the 19th-century "Indian"?

(See K&V 126-127 on Native performance art, of which this a good example!) |

• Note that I have a PowerPoint for the Preface & Chpt. 1 on CANVAS (Kidwell&Velie--Preface&Chpt1--hilited.pptx, in the "00 INTRO MATERIALS" folder)

• For my detailed K&V notes & commentary, see my outline of Chpts. 2-8 on CANVAS (K&Voutline--CH2thru8.docx, in the "00 INTRO MATERIALS" folder)

|

|---|

| "Turtle Island"?! (Kidwell and Velie 25) |

Note on the TRICKSTER archetype/NatAmer deity-motif (K&V 32-33, 108-109): In NatAmer folklore/myth in general, Coyote is the most common Trickster, a cosmic & natural force blessed with both sheer animal "stupidity" and uncanny animal cunning. In Lakota stories, for instance, he is forever losing his tail, getting chopped up into bits, and generally making a mess of the cosmic order. But he always comes back to life, and the world is better off for his shenanigans. (Also prominent as a Trickster in Lakota myth is Iktomi, the spider. In the Pacific Northwest, Raven [or Crow, or even Blue Jay] is Trickster.) The function of these tricksters has long been debated. My own reading relies on Jungian psychology, Bakhtinian dialogism, and ecology/ecocriticism. Jung reads the trickster as an aspect of the Shadow archetype—that "dark" complex of the unconscious psyche whose real role is to make the ego realize that it is out of balance, through its sheer repression of that "dark" side. The literary theorist Bakhtin claimed that the dominant social discourse towards order and reason necessarily entails a "polyphonic" (multi-voiced) reaction, in myth, literature, and society itself. Regarding this latter, he points to various cultural manifestations of "Carnival," wherein the common folk go "crazy" in an established ritual that is directed against the (repressive) social order. (Cf. Mardi Gras!) Finally, in a purely naturalist/ecological sense, the Trickster is "raw" instinctual animal, always erupting into "civilized" (and repressed) human consciousness as a magical & numinous force—again, as a corrective against an oh-so-blind ego-faith in order and rationalism: a reminder at last that WE are animals, that cosmic evolution needs entropy and chaos, that to remain in any blithe condition of stasis is a psychological and cultural death. Note on the TRICKSTER archetype/NatAmer deity-motif (K&V 32-33, 108-109): In NatAmer folklore/myth in general, Coyote is the most common Trickster, a cosmic & natural force blessed with both sheer animal "stupidity" and uncanny animal cunning. In Lakota stories, for instance, he is forever losing his tail, getting chopped up into bits, and generally making a mess of the cosmic order. But he always comes back to life, and the world is better off for his shenanigans. (Also prominent as a Trickster in Lakota myth is Iktomi, the spider. In the Pacific Northwest, Raven [or Crow, or even Blue Jay] is Trickster.) The function of these tricksters has long been debated. My own reading relies on Jungian psychology, Bakhtinian dialogism, and ecology/ecocriticism. Jung reads the trickster as an aspect of the Shadow archetype—that "dark" complex of the unconscious psyche whose real role is to make the ego realize that it is out of balance, through its sheer repression of that "dark" side. The literary theorist Bakhtin claimed that the dominant social discourse towards order and reason necessarily entails a "polyphonic" (multi-voiced) reaction, in myth, literature, and society itself. Regarding this latter, he points to various cultural manifestations of "Carnival," wherein the common folk go "crazy" in an established ritual that is directed against the (repressive) social order. (Cf. Mardi Gras!) Finally, in a purely naturalist/ecological sense, the Trickster is "raw" instinctual animal, always erupting into "civilized" (and repressed) human consciousness as a magical & numinous force—again, as a corrective against an oh-so-blind ego-faith in order and rationalism: a reminder at last that WE are animals, that cosmic evolution needs entropy and chaos, that to remain in any blithe condition of stasis is a psychological and cultural death. |

|

|---|

Wile E. Coyote—the Trickster

as Warner Bros. cartoon? |

TH, Jan. 27th:: TH, Jan. 27th::

• For my detailed K&V notes & commentary, see my outline of Chpts. 2-8 on CANVAS (K&Voutline--CH2thru8.docx, in the "00 INTRO MATERIALS" folder)

| *—Some Crucial LEGISLATIVE & LEGAL DECISIONS regarding Native regarding Native Religious Freedom—* |

|---|

| 1883-1934: | Federal ban on the Lakota Sun Dance (comparable restrictions on other tribes' major ceremonies standard during this same period) | | 1887: | Dawes Act: allotment (division) of Natives' lands in Oklahoma; similar laws regarding other Indian lands soon followed, the negative ramifications of which included a de facto repression of Native traditionalism | | 1892: | Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States: U.S. Supreme Court decision that included the declaration that "this is a Christian nation" | | 1934: | Indian Reorganization Act: as with the Dawes Act, this restructuring of reservation tribal governments further diminished Native traditionalism | | 1978: | American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA, which Vine Deloria, Jr., claimed is toothless) [K&V 75-76] | | 1978: | Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) [K&V 78] | | 1988: | Lyng decision: Supreme Court rules against Native rights to sacred/ceremonial sites on public lands (in favor, instead, of land developers [or rather/supposedly: the "greater good" of the public interest]) [K&V 76] | | 1990: | Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) [K&V 77; see V. Deloria's "A Simple Question of Humanity," written the year before] | | 1990: | Oregon v. Smith: Supreme Court ruling that state laws override any purported Native rights to use peyote for religious purposes (ergo illegal) [K&V 76] | | 1993: | Supreme Court allows/protects Native religious use of peyote; 1994: Congress agrees/"ratifies" [K&V 76; I don't have the whole background on this one, but I imagine that some version of the government's "proof of [Native] faith" prescription that Deloria often discusses has rendered this legalization nearly as problematic as the 1978 legislation.] |

|

|---|

|

|---|

| —Meme just shared w/ me by a student (thanks!); if you don't get it, see K&V 64-65. (Of course, "Wooster" should be "Worcester.") |

TU, Feb. 1st:: TU, Feb. 1st::

• Again, my detailed K&V notes & commentary, see my outline of Chpts. 2-8 on CANVAS (K&Voutline--CH2thru8.docx, in the "00 INTRO MATERIALS" folder)

|

|---|

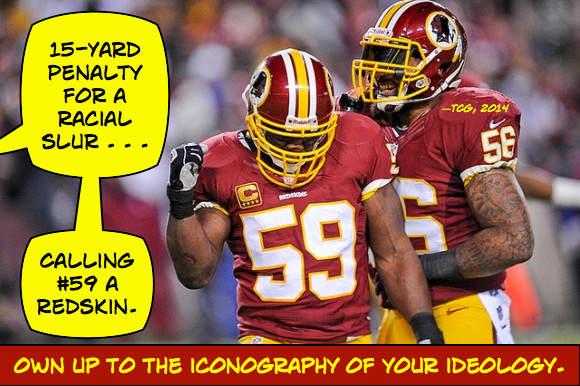

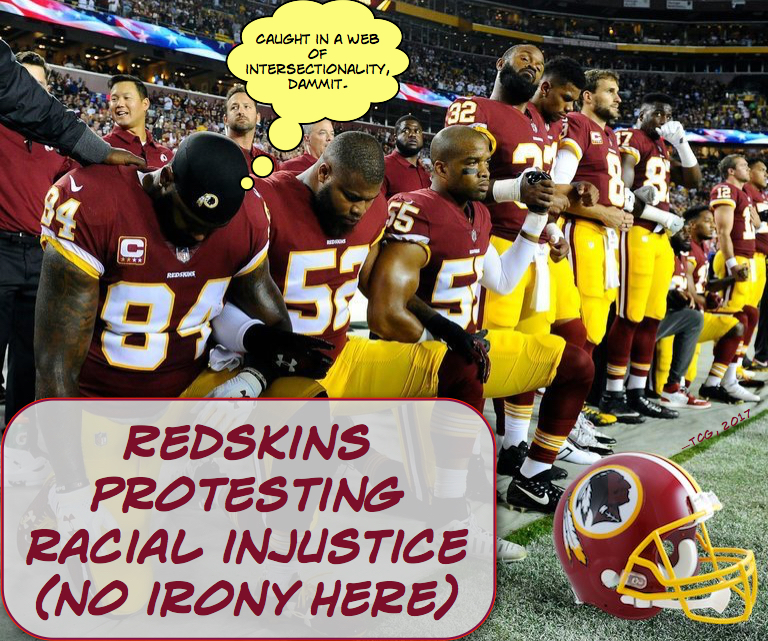

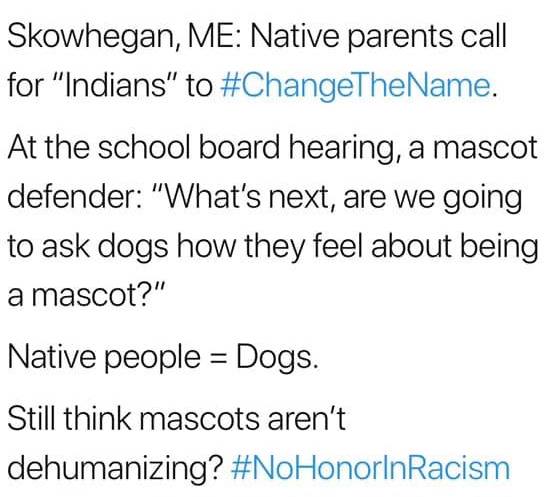

| —about the time of the 2021 Super Bowl . . . (Yeah, I know, I'm sorry: there are a lot of CHIEFS fans in Nebraska! But sooner or later, people are going to realize that "Chiefs" is damn near as racist as "Redskins," especially given the arrowhead iconography.) |

"Keep America Beautiful" (YouTube) "Keep America Beautiful" (YouTube) |

|---|

| —The "Crying Indian" (or the Eco-Indian)—the famous Earth Day PSA, 1971: both the tears and the Indian were fake. ("Iron Eyes Cody" was Italian; the "tear" was glycerin.) |

TH, Feb. 3rd:: TH, Feb. 3rd::

• One last time!: for my detailed K&V notes & commentary, see my outline of Chpts. 2-8 on CANVAS (K&Voutline--CH2thru8.docx, in the "00 INTRO MATERIALS" folder)

RESPONSE #1—Due TUES., 2/8 (uploaded to Canvas by midnight)—CHOOSE ONE (2 or more pages): RESPONSE #1—Due TUES., 2/8 (uploaded to Canvas by midnight)—CHOOSE ONE (2 or more pages):

—Don't worry about MLA formatting, headers, etc.; but do indicate which option you're doing, please.

a) Respond to K&V's Native American Studies by devising your own summary of what "Native American Studies" actually is, or should be. (As your OWN summary, it will necessarily highlight some of K&V's central points and de-emphasize, if not even denigrate, others.) Refer to various passages from the book in making your argument. (I can imagine this as a tongue-in-cheek response, if you're so inclined, as long as you maintain a proper respect for the subject!)

b) Evaluate K&V's text as an introductory textbook. That is, is it a good or bad example thereof? Why? If if it is bad or only pretty good example, what would you change to make students more engaged with Native American Studies? Again, refer to various passages from the book in making your argument.

c) Free (but focused) Response: develop your own topic-choice as a focused response on some aspect or related aspects of K&V—for example, some specific issue or event or phenomenon that you found especially interesting.

d) As mentioned on the syllabus, another option is to turn in a do-your-own-thing "READER'S JOURNAL" that addresses a "goodly" range of the K&V chapters (and earlier readings?), including via creative responses. (These should ideally be responses you wrote immediately after reading, so there's no danger of simply rehashing class ideas [see final caveat below]!)

e) Use K&V (again, in a concerted fashion!) in your reaction to a current "Indian Country" controversy or issue. (See, for example, my "In the News" links above. (For example, how does students wearing Native regalia at a graduation ceremony relate to the "grander issues" discussed by K&V?! Or: how about non-Natives going on vision quests [the Yellowstone article linked above]?)

f) Use K&V (again, in a concerted fashion!) to respond to our last President's Columbus Day pronouncement. (Don't worry if you're a fan of the Donald: I severely doubt that he wrote the proclamation himself.)

—Note: For all responses, please include p#'s in parentheses for any specific references to K&V. (This also demonstrates that you BOUGHT the BOOK!) Also, please avoid simply rehashing ideas brought up in class or in my outlines of K&V provided only. Feel free to object to/expand upon these, of course, but above all, try to do "something else" that still demonstrates that you've done the reading.

|

|

|---|

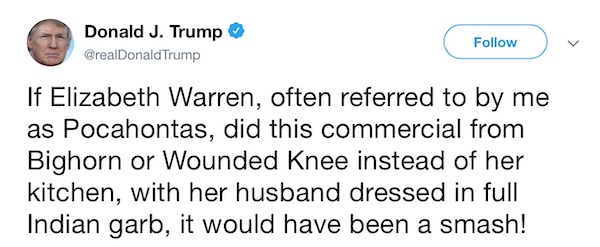

"I'm glad Native American Studies doesn't have to combat stereotypes anymore!"

(For starters, what does Pocahontas's east-coast Powhatan tribe have to do, at all, with Wounded Knee or the Little Bighorn?And of course, nor does Warren's claim of Cherokee blood have any relation to Pocahontas.) |

|

|---|

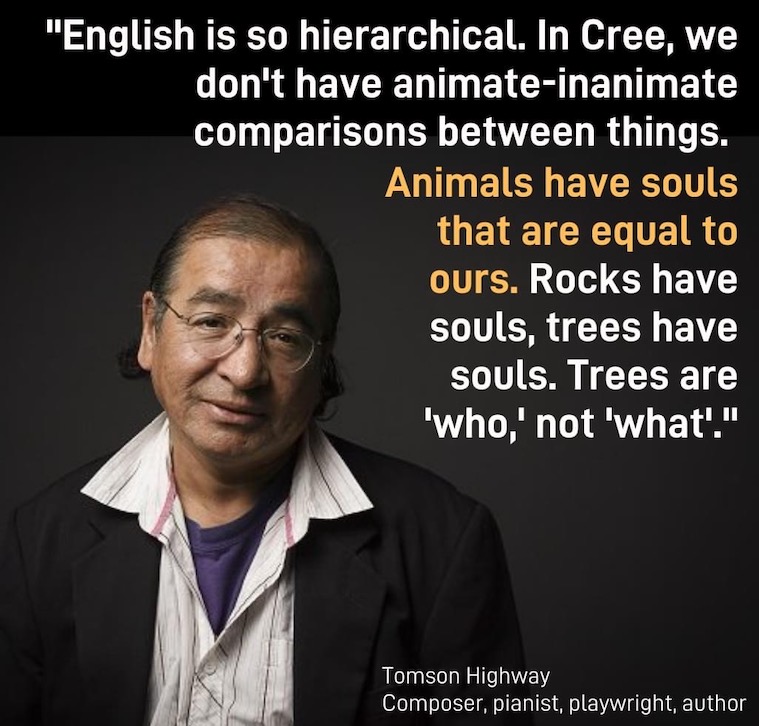

| Language = epistemology. |

TU, Feb. 8th:: TU, Feb. 8th::

Newcombe: "500 Years of Injustice" (Native American Voices 101-104) Newcombe: "500 Years of Injustice" (Native American Voices 101-104) |

|---|

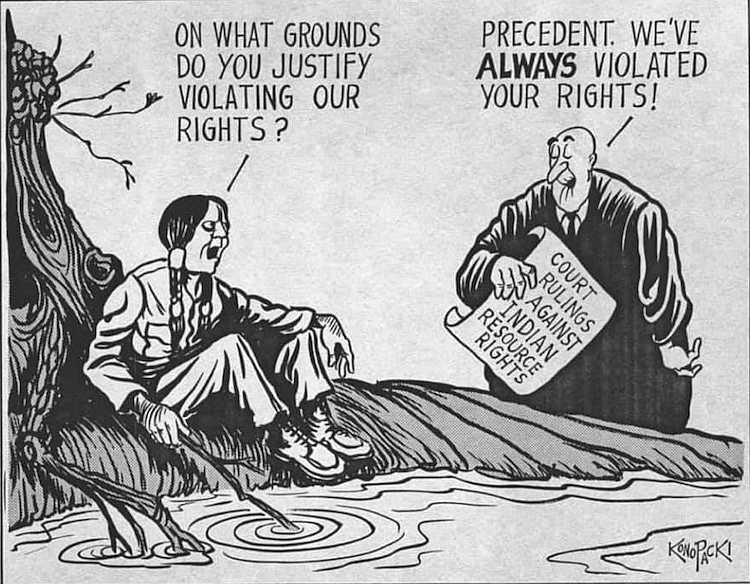

| | • Newcombe traces a series of causes and effects: Euro-colonizers' 15th-century Doctrine of Discovery led to Justice Marshall's Supreme Court decisions of 1823 (which basically rehearsed the DofD) and of 1831 (which claimed the U.S.'s "plenary" [absolute] power over tribes); this led to the breaking of treaties (incl. Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868) & land theft. Newcombe calls for an end to this "unconstitutional" series of legal precedents, in part through an appeal to the "separation of church and state" clause in the Constitution (103B). | | | • Note also the date of the essay: 1992 (500 years after Columbus "sailed the ocean blue"); thus the powerful indictment in the ¶ beginning "During this quincentennial" (101B-102A). |

|

|---|

| —Ha! Pretty much in accord with the Newcombe & Wilkins essays, etc. |

|

|---|

| —The headline is real; I just changed the list in the photo. |

Wilkins: "A History of Federal Indian Policy" (NAV 104-112) Wilkins: "A History of Federal Indian Policy" (NAV 104-112) |

|---|

| | • A well-organized & detailed intro to its topic by an obviously serious academic historian; the essay/chapter covers a lot of dates & events "we already know," but no source so far is as comprehensive in its historical/legal coverage. For example, see the two ¶s on the pros and then the cons of the Indian Reorganization Act (110). | | | • While the tone seems much more "objective, fair and balanced" here (as is the case w/ most academic historians), note that Wilkins agrees with Newcombe that Marshall's 1823 decision is based on the old "Doctrine of Discovery" (and is thus questionable) (106B) and that the Constitution's "separation of church and state" clause is apparently a crock in its (lack of) application to Native Americans (107B-108A). | | | • Oops: The Trail of Broken Treaties protest march took place in 1972, not 1973 (111A). | | | • Wilkins' conclusion seems right on about the "ambivalence" of U.S. federal policy regarding Native sovereignty, et al.: "The policy ambivalence evident in the conflicting goals of sometimes recognizing tribal self-determination and sometimes seeking to terminate that governing status has lessened only slightly over time. Tribal nations and their citizens find that their efforts to exercise inherent sovereignty are rarely unchallenged, despite their treaty relationship with the United States" (112B). |

|

|---|

| Something close to this almost happened after Custer's massacre of Black Kettle's Cheyenne band at the Washita. |

|

|---|

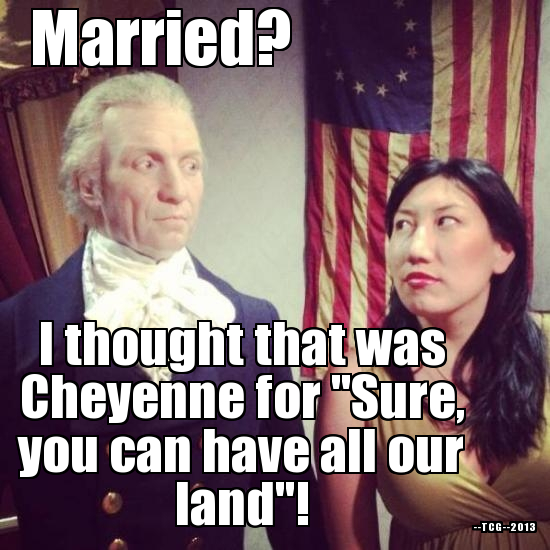

| —my text/design-edit of a Facebook-shared meme |

|

|---|

| —my (old, bad) photo of the Lewis & Clark statues—w/ a satirically accommodating Native dude—down by the Great Plains Art Museum |

Floyd Red Crow Westerman (w/ Trevy Felix): "Missionary" (Hen House Studios [YouTube]) Floyd Red Crow Westerman (w/ Trevy Felix): "Missionary" (Hen House Studios [YouTube]) |

|---|

| —Written soon after Vine Deloria, Jr.'s Custer Died for Your Sins, this song's lyrics could have been ghost-written by Deloria, I swear! (In fact, Westerman's 1969 album was also called—Custer Died for Your Sins!) |

TH, Feb. 10th:: TH, Feb. 10th::

Gonzales: "The Black Hills" (NAV 113-119) Gonzales: "The Black Hills" (NAV 113-119) |

|---|

| | • Like Newcombe's essay, this is certainly written from a position of activism & advocacy. (See especially the ¶ about "plunder" [116B]; the ¶ on "the Spirit of Crazy Horse" [117A]; and the ¶ w/ the phrase "officious intermeddlers" [118A].) Gonzales's essay is certainly the most "pro-Indian" of the three, but his evidence regarding the breaking of the Fort Laramie Treaty in the U.S.'s "land grab" of the Black Hills (114) is pretty damning. (But so was the U.S. Supreme Court's own 1980 decision that found the U.S.'s seizing of the Black Hills to be the most "ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealings . . . in our history" (114B). | | | • The "Powder River War" is better known (by me, at least!) as Red Cloud's War—which, according to Gonzales, "was the first military conflict that the United States ever lost" (114). By "conflict," G. obviously means an entire war, not a single battle. Other sources have claimed the War of 1812 (against Great Britain) as the U.S.'s first lost war; it seems at least a draw? In any case, partisans who claim that the Vietnam War was "our" first loss seem pretty short-sighted. | | | • Note: the long Brown Hat quot. is confusing—"I went to the Black Hills and cried, and cried, and cried"—unless you know that it refers to Brown Hat going on a vision quest, which, in one Lakota formulaic expression, is "to cry for a vision." | | | • Newcombe's final calls to action regarding Bear Butte incl. appeals to the religious freedom clause of the 1st Amendment and to the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 (118B). | | | • In conclusion: "The Lakota tribes' rejection of the $100 million ICC [Indian Claims Commission] award for the Black Hills in 1980 has come to symbolize Native American resistance in North America" (119A); and indeed, "the long-term survival of the Lakota people depends on how the Black Hills claim is ultimately resolved" (119B). | | | • Hey, w/ "compound interest," the $100 million is now—er, was when the essay was written, in 1996!—$380 million (119B). Hmmm. . . . |

Bear Butte, SD (TCG, 2009, 2011; select thumbnail for larger photo)

| |  Charles A. EASTMAN—(from From the Deep Woods to Civilization:) "The Ghost Dance War" (Trout 266-76)— Charles A. EASTMAN—(from From the Deep Woods to Civilization:) "The Ghost Dance War" (Trout 266-76)—

—tone/attitude/word choices—"whose side is he on?!" (par. 3: "wild Indians"; par. 8: "wilder element"; par. 12: "ghost dance craze"; par. 22: "wilder Sioux"); par. 13: "malcontents" [incl. Big Foot, Kicking Bear (who had, by the way, travelled out West to meet with Wovoka), and the son of Red Cloud]—vs. par. 13, par. 15: "Friendly"'s [incl. American Horse; Red Cloud?!] . . . [BUT—par. 12: "poor natives" vs. white "politicians"; par. 25, 35: "so-called" hostiles; after massacre: par. 29: "poor creatures" (a change in tone/attitude after massacre?)] . . . You might also the ponder the perhaps greater import, in terms of Eastman's assimilation, of the following words of a white woman back East: "'I know one Sioux who has not been conquered, and I shall not rest till I hear of his capture!'" (par. 21)—the irony of which escaped Eastman himself!?

—Consider the statement towards end (par. 34): "All this [the slaughter] was a severe ordeal for one [Eastman] who had so lately put all his faith in the Christian love and lofty ideals of the white man." HOWEVER, he immediately continues: "Yet I passed no hasty judgment. . . ."!?

—ironic contrasts: "Christmas season"! (par. 20); E.'s white intended, who's half "Puritan," half Tory! . . . betrothal: "Christmas day of 1890" (par. 22) (massacre: Dec. 29th—the morning of which was "sunny and pleasant"! [par. 25])

—à la today?: note the deleterious role of the press (par. 17, par. 30)

—results/description of massacre per se: par. 31-32 (no comment); incl. survival of 1-yr.-old baby . . . cavalry: 25 dead, too—but mostly from friendly fire!*—Black Elk, in Black Elk Speaks, also describes a pathetic scene, of "Dead and women and children and little babies"; "I saw a little baby trying to suck its mother, but she was bloody and dead." —telling final two words of essay: "superior force"

—Finally, note the Christian ground springs of the (therefore syncretic) Ghost Dance religion: Wovoka not only called himself a "messiah" and the "Indian Jesus," but referred to Christ frequently; the GD movement therefore both thoroughly messianistic and millennialist (that 1,000 or 2,000-year thing, in which "a new day will dawn" [Led Zep!])—two notions fairly alien to traditional Native thought. (Indeed, the 1st paragraph of Eastman's chapter—omitted by Trout—begins: "A religious craze such as that of 1890-1891 was a thing foreign to the Indian philosophy" [From the Deep Woods 92].) |

|

|---|

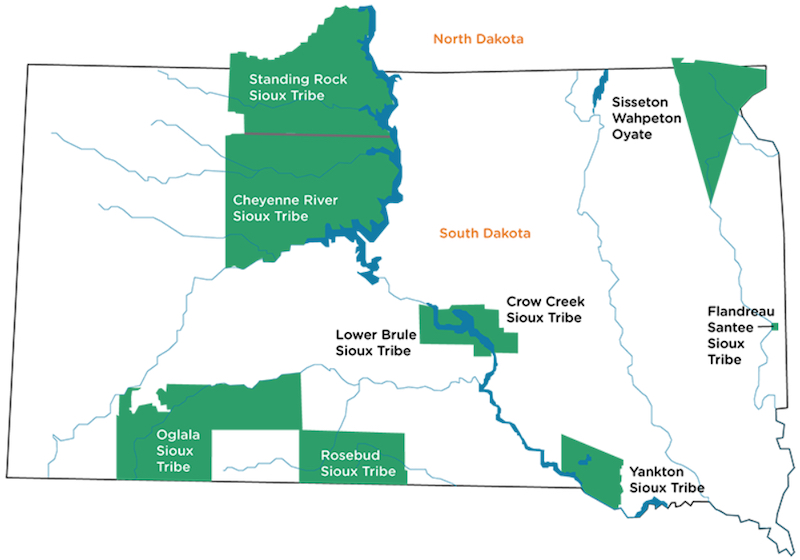

| —South Dakota reservations (for Eastman essay, etc.) |

Famous photo of slain Mnikoju Lakota chief Big Foot (Si Tanka) at Wounded Knee.

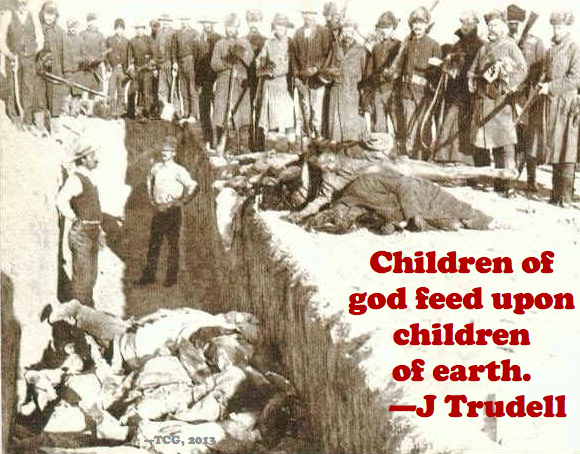

* more Images of Wounded Knee, incl. the open mass-grave trench (or see my meme, below)

|

|---|

—photo "borrowed" from Google Images

(Wounded Knee mass burial) |

Elizabeth Cook-Lynn: "New Indians, Old Wars" (NAV 194-198) Elizabeth Cook-Lynn: "New Indians, Old Wars" (NAV 194-198) |

|---|

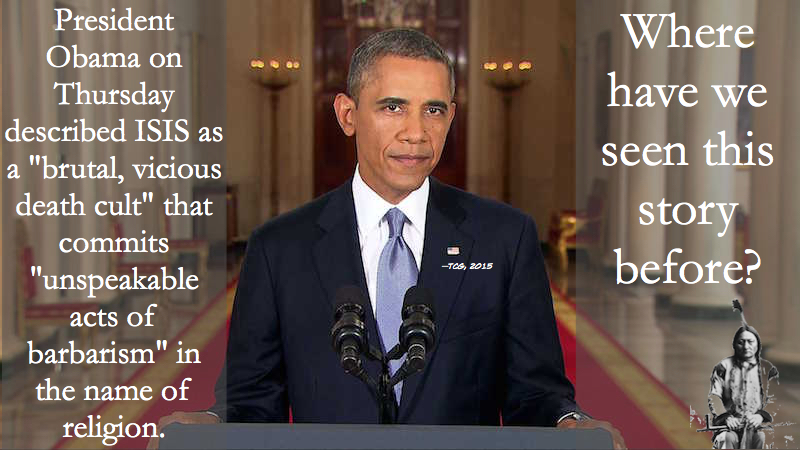

| | • 9/11/2001—the U.S.'s response to the Twin Towers attack: C.-L. finds "a connection between this defensive act and the U.S. response to the killing of . . . Custer [at the Little Bighorn] in 1876" (194A). (Wow. Pretty incendiary stuff?! Indeed, her "angry," in-your-face tone far surpasses that of, say, Newcombe or Gonzales, to the point of being a bit too heavy-handed at times?) | | | • Speaking of Native history—C.-L. turns to the Black Hills land/suit "issue" (194-195A), noting (as Gonzales did) that $ "compensation has been the only remedy available . . . a remedy rejected by the entire Sioux Nation for many decades" (194B). (Uh, the Lakota Nation[s], specifically; maybe only a Dakota writer like C.-L. would use "Sioux" here?! [Okay, she is from an older generation. . . .]) Also, as with Gonzales, C.-L. notes that even the U.S. Supreme Court admitted it to be land "theft" in 1980 (195A). | | | • Regarding the 1950s "relocation laws," C.-L.'s claim that "two-thirds of the entire Indian population" of the U.S. "was relocated to cities in the West" seems a bit high (195B)! (See my Healey PowerPoint.) | | | • Now as for the essay/book title: These are the matters of "old wars" taken up by "new Indians" who know and remember that thousands have died terrible deaths on this unlucky journey" of Euro-colonization (195B). (And now her numbers estimate might be a bit low!?) | | | • The U.S. dilemma (oh, "sweet land of liberty" and high-blown ideals): the historical treatment of Natives is difficult fact to handle for "a powerful nation claiming an honorable place [indeed, the highest place of idealistic values!] among nations throughout the globe." C.-L. even dares to use the word "genocide": it's an historical fact that the U.S. "has pursued policies throughout the generations that led to the decimation of the first nations on this continent" (195B). | | | • "Anti-Indianism" is C.-L.'s term (from a previous book of hers) for racism against Native Americans; here she claims it to be a basic "concept in American Christian life, just as Islamophobia and anti-Semitism are concepts in Christian Europe" (196A; wow). | | | • Now she turns to the [doctrine of] "'discovery period'"—when the colonizers refused to really know the Native Americans, but instead projected such qualities as "simple and good," or "savage and cruel, or "ignorant and deficient," or—"not human" (196B). | | | • Back to the Native history/current Middle East analogy that began the essay: the new U.S.-enforced Iraqi constitution "is much like the illegal, colonial IRA constitutions written for and by" Native American reservations "eighty years ago, charts for democracy that have, unfortunately, failed to meet the needs of the people." Indeed, unless the U.S. "begins to understand that its victims will no longer accept the idea begun [in] 1492 that 'inferior' races and civilizations can be wiped off the face of the earth, it will face constant war" (196B). | | | • Why this "repeat of history"? It "may be that the ideology of civilizing and Christianizing negatives so deeply embedded in the Euro-American experience is a consistent" reflection of Euro-Americans' "continuing social needs and aspirations" (197A; a rather vague statement in need of unpacking, no doubt). | | | • The crux: "The people in the Middle East" now invaded by the West "are not uncivilized, and neither were the Indigenous peoples of North America. They are not savages, and neither were" Native Americans. "Iraqis are not without god, language, or culture. Neither were the peoples of the Americas" (197B). (And yet, after the 9/11 attacks—and supporting C.-L.'s argument—the Bush Administration consistently employed a binary rhetoric of "civilization" versus "barbarism.") | | | • Conclusion & Thesis: "the unfortunate people called the 'terrorists' of the twenty-first century in Baghdad have become what the 'savages' of the northern Plains were thought to be so long ago" (197B). | | | • Ultimately what matters is who controls the message (and who gets to call the other side "terrorists"!?): "who controls the language by which the stories are told is still the ultimate power" (197B). And so: "New Indians must tell the new history about the old wars because they have been witness to savagery and terrorism—and continue to be" (198A). (Note C.-L.'s re-inscription/reversal of "savage" & terrorist" throughout this essay—a move anticipated by our next author, Zitkala-Ša, when she basically asks out loud, regarding some rude white students, "Who are the real barbarians here?!") | | | • Finally—"Make no mistake: a holocaust happened here in our own lands and it continues here and elsewhere" (198). |

| |

Joy Harjo: "I Give You Back"(from How We Became Human 50-51) |

|---|

| | —As in other famous poems of hers, like "Remember" and "She Had Some Horses," note the characteristic "oral"-repetition style; this poem is often read as JH.'s own reply, her own "getting over," the personal demons/complexes of "She Had Some Horses," via a powerful personification of—and inner dialogue with—her own "fear": "I release you." | | | —[Old student question:] What does the stanza beginning "Oh you have choked me, but I gave you the leash" mean? | | | —[My question:] The "I am not afraid" repetitions often combine opposites, "black" & "white," etc.—an all-encompassing interrelatedness, as it were. Does this include, then, forgiving/accepting the cruel facts of colonization ("raped and sodomized," etc.)? | | | —[My question:] Aside from the "oral" repetition, does the number FOUR work its way into this poem? [Yes, in the 4x refrains of "I release you" (50) and, even, "my heart" (51).] |

Joy Harjo: "Fear Song" (YouTube) Joy Harjo: "Fear Song" (YouTube) |

|---|

| —A later set-to-music version of "I Give You Back," from Joy's CD Native Joy for Real (2004) |

| |

Adrian C. Louis: "Red Blues in a White Town the Day We Bomb Iraqi Women and Children"(from Among the Dog Eaters, 1992) |

|---|

| | —Epigraph/quot. of Iraqi widow: the tables turned, the Orientalization of the Native American by "Orientals"! . . . middle section of poem: the bullying of the Native boy by three white boys—note the "muddying" of the history book!—until he fights back, to the admiration of the narrator . . . then the political shift in the final strophe, a protest against U.S. policies during the first Iraqi war—carried out by "Long distance killers with college degrees"—and the clear parallel between such a war and government policies towards the Native American (see Cook-Lynn's essay): they are a "sand tribe," after all; and the strange conclusion: what/which "God" is this?—when "a sand tribe's blood splashed up / to white clouds / to blue sky / to God's face" (invoking again the red-white-and-blue mock-patriotism of the poem's title)? |

|

|---|

| —my meme-tribute to Adrian when he died a few years ago (2018) |

John Trudell: "Rich Man's War" (YouTube) John Trudell: "Rich Man's War" (YouTube) |

|---|

| —After a stint as the President of A.I.M., Trudell went on to become a poet-songwriter, whose lyrics were quite in accord w/ A.I.M.'s "radicalism." |

TU, Feb. 15th:: TU, Feb. 15th::

| Zi[n]tkala-Ša [zee(n)t-KAH-lah SHAH] = "bird-red" (Red Bird) |

|---|

| * TRIBE: "Yankton Sioux" (the Yankton & Yanktonais bands of SE SoDak) = Nakota tribe ([see Dominguez xix (the intro in our edition)], though usually called Dakota, even by Zitkala-Ša herself); blood quantum!: "one half Sioux" (Fisher xix) | | * LIFE: | | | 1876: born Gertrude Simmons (her step-father's last name), on the Yankton Reservation (SE SoDak)—the same year, by the way, as the Battle of the Little Bighorn | | | 1884: missionaries show up; and so to an Indian boarding school—White's Manual Institute—in Indiana (which she attended, with some intervening years at home, to 1895) | | | [1890: the Massacre of Wounded Knee, about which Zitkala-Ša is oddly "reticent": "Nowhere in these stories is there a reference to this historical act of genocide" (D&N xxxiii).] | | | 1895-1897: to Earlham's College (Indiana), and to poetry writing & oratory contests | | | 1897-1899: teaching at Carlisle Indian Industrial School! | | | 1899-1902?: study at the New England Conservatory of Music (violin) | | | 1900-1902: composes bulk of her literary output [see next list] | | | 1902: married to Raymond Bonnin, which some claim signaled the "decline" of her literary career (Fisher xiii) | | | 1903-1916: living with husband, now a B.I.A. employee, on a Utah reservation. where she further develops her bent for Indian activism—including her . . . | | | 1913-1918: activist denunciation of Native peyote use, for which the "liberal ethnologist James Mooney . . . denounced" her "as a fraud," for wearing an Indian outfit that was a hodge-podge from different tribes (D&N xxi-xxiii)! | | | 1916: Bonnins move to Washington, D.C., upon Zitkala-Ša's election as secretary & treasurer of the Society of the American Indian—"the first national pan-Indian political organization run entirely by Native people" (D&N xxix-xv; founded 1911, "dissolved" in 1919); and a new, more public life of activism on behalf of Native Americans, including calling for Indian citizenship (granted 1924) and the removal of the Sun Dance ban (legalized 1934, via the Indian Reorganization Act) | | | 1926: founds the National Council of American Indians, for which she was president until her death in . . . | | | 1938: died; "In perhaps the greatest misrepresentation of a life often misrepresented, she was described in the hospital's postmortem report as "'Gertrude Bonnin from South Dakota—Housewife'" (D&N xxviii)! | | * WORKS: | | | 1900: Atlantic Monthly: "Impressions of an Indian Childhood"; "The School Days of an Indian Girl"; "An Indian Teacher among Indians" [all later included in American Indian Stories] | | | —Praise(?!) of Zitkala-Ša in an issue of Harper's Bazaar in 1900: "Zitkala-Ša is of the Sioux tribe of Dakota and until her ninth year was a veritable little savage" (qtd. in Fisher vii; see also Helen Keller's letter in the old advertisement in the back of our text). | | | 1901: book: Old Indian Legends; Harper's Magazine: "The Soft-Hearted Sioux" [later included in American Indian Stories] | | | 1902: Atlantic Monthly: "Why I Am a Pagan" | | | —Carlisle founder Richard Pratt's review of this essay: "its author was 'worse than a pagan'" (D&N xix). | | | 1913: collaborated with William Hanson on the "Indian opera" Sun Dance (revived on Broadway in 1937 [Fisher]—or 1938? [the year of her death: D&N]) | | | 1921: book: American Indian Stories | | | —"[S]he calls her new book the 'blanket book' (the cover image was an image of a Navajo blanket)" (D&N xxvii; note: traditional Indians were often referred to as "blanket Indians"). | | | —". . . one of the first attempts of a Native American woman to write her own story without the aid of an editor, an interpreter, or an ethnographer" (Fisher vi) | | | —Her work "lay in some obscurity after her death in 1938 before being rediscovered and reassessed in the 1970s and 1980s" (D&N xiii). | | * HER TWO WORLDS: | | | —"Zitkala-Ša had every right to feel nervous about her mission to become the literary counterpart of the oral storytellers of her tribe because she felt compelled to live up to the critical expectations of her white audience" (Fisher vii). | | | —"To her mother and the traditional Sioux on the reservation . . . she was highly suspect because, in their minds, she had abandoned, even betrayed, the Indian way of life by getting an education in the white man's world. To those at the Carlisle Indian School . . . on the other hand, she was an anathema because she insisted on remaining 'Indian,' writing embarrassing articles such as 'Why I Am a Pagan' that flew in the face of the assimilationist thrust of their education" (Fisher viii). . . . "Zitkala-Ša has been accused of 'selling out' largely because of the difficult balancing act she attempted as a mediator between tribal, bureaucratic, and activist concerns" (D&N xxiv). | | | —Name change—after quarrel with sister-in-law: "I bore it [the name Simmons] a long time till my brother's wife—angry with me because I insisted upon getting an education—said I had deserted home and I might [as well] give up my brother's name 'Simmons' too. Well, you can guess how queer I felt—away from my own people—homeless—penniless—and even without a name! Then I chose to make a name for myself—and I guess I have made 'Zitkala-Ša' known . . . " (qtd. in Fisher x). . . . Also noteworthy: her brother's (only) given name was actually David; "Zitkala-Ša fictionalized him as Dawée" (D&N xv)! | | | —Religion: "We can do little more than attempt to keep up with her rapid moves between Catholicism, paganism, Mormonism, and Christian Science" (D&N xv). | | | —"Though she would spend her life working for the rights of Indians and would become one of the most vocal spokespersons of the Pan-Indian movement in the 1920's and 1930's, Zitkala-Ša was never reconciled with her mother. She spent her life in balance between two worlds, using the language of one to translate the needs of another. She was in a truly liminal ['border'] position, always on the threshold of two worlds but never fully entering either" (Fisher xiii). | | | —"Controversial to the end, Gertrude Bonnin remained an enigma—a curious blend of civilized romanticism and aggressive individualism. Her own image of herself eventually evolved into an admixture of myth and fact, so that by the time of her death in 1938, she believed, and it was erroneously stated in three obituaries [in major Eastern newspapers], that she was the granddaughter of Sitting Bull . . . though her own mother was older than Sitting Bull [and they weren't even from the same tribe!]" (Fisher xvii). . . . "Zitkala-Ša herself was implicated in propagating this myth. It became one of her favorite autobiographical stories. . ." (D&N xiv). | | | —"Her career also exemplifies the tremendous difficulty confronting minority people who would become writers but who are constantly under pressure from their own groups to use literature toward socio-political ends. . . . The wonder is that she wrote at all and in so doing became one of the first Indians to bring to the attention of a white audience the traditions of a tribe as well as the personal sensibilities of one of its members" (Fisher xvii-xviii). | | | —Subversion/"Reinvention"?: [regarding "School Days":] "Resisting the pressures of assimilation in small ways, employing trickster strategies such as vandalizing the school's Bible, she was able to maintain a sense of herself" (D&N xvi). | | SOURCES: | | | Fisher = Dexter Fisher's Foreword to the previous U of Nebraska P edition of American Indian Stories | | | D & N = Davidson & Norris's Introduction to American Indian Stories, Legends, and Other Writings (Penguin Classics) | | | | (A more legible/printable version of this handout/outline is on CANVAS, in the "05 ZITKALA-S(H)A" folder.) |

| ** Z-SHA PRE-READING NOTE: I tend to approach longer literary texts—like Z-Sha's three-part autobiography—as a structuralist of sorts, identifying its building blocks, which I like to call "MOTIFS" (as in musical motifs: snippets of melody or chord progressions that get repeated throughout the "symphony" that is the text). In Z-Sha, for instance, it's interesting to follow her DICTION (word choices: e.g., "wigwam," "paleface," "iron horse": WHY? who is her AUDIENCE?); her common FIGURES OF SPEECH (e.g., the recurring comparisons, implicit or explicit, to "wild animals"); her use of literary conventions (e.g., those Victorian over-dramatic, emotional moments?!; the Biblical plot motif of temptation & disobedience). Also, speaking of her audience, how might that have affected her TONE and POINT OF VIEW? How would you characterize her tone (attitude)? How does her tone & PofV change thru the three sections? |

| * "Impressions of an Indian Childhood" [1900] (AIS 7-24) |

|---|

| | I: "My Mother" (7-11) | | | | —intro setting "exotic" (for her Eastern white audience), a "wigwam" by the "Missouri" (7) [Why "wigwam" [7, 9, 12, etc.] (an Abenaki dwelling/word [northeastern Algonquian tribe]) instead of the Dakota word "tipi" (which she will use later)?!] | | | | —Mother's characterization (any stereotypes for her audience?): "sad and silent [stoic!]" (yet tearful) (7)—why? | | | | —Z-Ša's characterization (any stereotypes for her audience?!): a "wild little girl of seven," "light-footed," "free as the wind" and as "spirited" as "a bounding deer"; full of "wild freedom and overflowing spirits" (8) | | | | —Cousin "Warca-Ziwin" (Sunflower) [Lakota: wahcazizi (wahkCHAHzeezee), "yellow flower"; or wahcazi tanka (wahkCHAHzee TAHNka), "big flower"] | | | | —Reason for mother's sorrow: the actions of the "paleface" [again note the Western-dimestore-novel word choice (9, 39, etc.)]; Z-Ša's reaction: "'I hate the paleface that makes my mother cry!'" (9) . . . "the paleface has stolen our lands and driven us hither[!—word choice!]"—"like a herd of buffalo" [Native = animal, an eventual motif] . . . and the death of Z-Ša's sister and uncle, upon the tribe's reaching "this western country" (10). [Note: the Dakota were previously inhabitants of Minnesota, mostly, until forced to various reservations in eastern SoDak & NoDak.] | | | II: "The Legends" (12-17) | | | | —Indian Ed. 101: Z-Ša hears the "old legends" (13). | | | | —Emphasis on Dakota "hospitality" towards relatives & friends, especially "old men and women"—and the young's respect, "proper silence" (12-13) | | | | —"Iktomi story" (15) note: Iktomi is the Dakota/Lakota Trickster figure in the guise of a spider (or "spider-man"); he is the "anti-hero" of many of the stories in Z-Ša's Old Indian Legends. | | | | —Z-Ša's fearful reaction to the "secret" sign of the "tatooed" "blue star" (16-17; Z-Ša's apparent obsession with this story/image continues in her short story about the "Blue-Star Woman" [159-]). | | | III. "The Beadwork" (18-24) | | | | —Indian Ed. 102: bead-making with her mother, whose pedagogical methods seem more Rousseauian than authoritarian—encouraging Z-Ša's own "original designs" (19) and—most of the time—treating her "as a dignified little individual" (20) | | | | —2nd episode: the girls on their own, "impersonating" their "own mothers" (modeling!) (21-22); but then they give way to their "impulses," shouting and "whooping"—cavorting "like little sportive nymphs on that Dakota sea of rolling green" (22-23; again note Z-Ša's [oddly assimilationist and culturally hybrid] word choices). | | | | —Chasing her shadow (23-24): a rather predictable & mundane narrative, unless it has further metaphorical resonances? . . . |

|  |

|---|

| TIPI (many Great Plains tribes) | WIGWAM (many Eastern Woodlands tribes) |

|---|

Wounded Knee (Part 5 of PBS series We Shall Remain [YouTube]) Wounded Knee (Part 5 of PBS series We Shall Remain [YouTube]) |

|---|

Wounded Knee. Dir. Stanley Nelson. Part 5 of We Shall Remain. American Experience/WGBH International, 2009. DVD. The section shown before class was 31:50-39:25; during class (the boarding school flashback): 39:02-45:27. |

TH, Feb. 17th:: TH, Feb. 17th::

| * "Impressions of an Indian Childhood" [1900]--continued (AIS 25-45) |

|---|

| | IV. "The Coffee-Making" (25-29) | | | | —two separate tales again, of the poor "haunted" fellow (25-26) and Za-S's untoward attempt at hospitality (27-29) | | | | —Z-Ša's fear of the "crazy man," Wiyaka-Napbina [Lakota: wiyaka (WEE-yah-khah) = feather(s); wanap'in (wah-NAH-p'ee[n]) = necklace)], whom her mother says really should be pitied, having been "overtaken by a malicious spirit" (25-26) | | | | —Z-Ša's coffee-making = "muddy warm water" for the visiting old man (27-29)—and the others' polite respect for her efforts, nonetheless: "But neither she [her mother] nor the warrior, whom the law of our custom had compelled to partake of my insipid hospitality, said anything to embarrass me" (28). | | | | —NOTE: "How!" (28) now more commonly (and less confusingly) spelled "Hau!"—Lakota/Dakota word of both greeting ("hello") and assent ("you betcha"). | | | V. "The Dead Man's Plum Bush" (30-33) | | | | —Name note: "Wambdi" (30) = Lakota wanbli (wah[n]BLEE): eagle | | | | —"Chaperon" custom for young women (31) | | | | —Z-Ša & mother on their way to a communal feast—characteristically stopping on their way to give food to a sick old woman (31-32); her mother's story of the plum bush whose "roots are wrapped around an Indian's skeleton, and Z-Ša's attempts to hear the "strange whistle of departed spirits" (32-33). [Hmmm: but later, Z-Ša will NOT listen to her mother's warnings about ANOTHER "forbidden fruit" (32)!] | | | VI. "The Ground Squirrel" (34-38) | | | | —Character description of aunt, who's more jovial than her mother (34-35) | | | | —Z-Ša's daily "sharing" of corn with the ground squirrel, that "little stranger": "I wanted very much to catch him and rub his pretty fur back" (36)! | | | | —Strange(?) comment that she has "few memories of winter days" from her SoDak childhood; recounts her confusion of river ice with the missionaries' marbles (37). . . . | | | | —word choice again: "many a moon" (38; see also 74)!? | | | VII. "The Big Red Apples" (39-45) | | | | —Apples as the (Biblical) "forbidden fruit"—the "temptation of assimilation" (D&N xxx) (Also, "apple" = Indian slang for someone "red on the outside but white on the inside.") | | | | —The "paleface missionaries": "come to take away Indian boys and girls to the East"—mother agin' it! . . . Z-Ša hears promises of "a more beautiful country," a "Wonderland" (39, 40). [= Oz!?—"You won't be in Kansas—er, SoDak—anymore!"] | | | | —Dawée having already studied there, even Z-Ša's mother has become a bit assimilated, now living like "a foreigner, in a home of clumsy logs" (40). | | | | —But mother's WARNINGs: beware the "'white man's lies. Don't believe a word they say. Their words are sweet, but . . . their deeds are bitter. . . . Stay with me, my little one!'" (41). | | | | —Notice Z-Ša's "retrospective" statement: "Alas! They came, they saw, they conquered" (41)—which not only is pregnant with the pain of her future experiences back East, but expresses her later assimilation in her very use of a quot. from Western Civ. (Julius Caesar's veni, vidi, vici). | | | | —word choice: "iron horse" (42; etc.) | | | | —Judéwin's details regarding the "red, red apples" (41-42) | | | | —1st inkling of the eventual "theme" of disobedience (cf. Genesis!): "so unwilling to give up my desire that I refused to hearken to my mother's voice" (43). | | | | —Finally, her mother's grudging assent—and her pessimistic reason: "'She will need an education when she is grown, for then there will be fewer real Dakotas, and many more palefaces.'" Her hope for justice?: "'The palefaces, who owe us a large debt for stolen lands, have begun to pay a tardy justice in offering some education to our children.'" BUT: "'I know my daughter must suffer keenly in this experiment'" (44). | | | | —Oh!—any symbolism here, as Z-Ša leaves for the East?!: "I saw the lonely figure of my mother vanish in the distance" (44). | | | | —Z-Ša's immediate (and premonitory?) "regret": "I felt suddenly weak. . . . I was in the hands of strangers whom my mother did not fully trust. I no longer felt free to be myself, or to voice my own feelings." And a final "animal" simile (and the "wild"): "I was as frightened and bewildered as the captured young of a wild creature" (45). |

| * "The School Days of an Indian Girl" [1900] (AIS 47-80) |

|---|

| | I: "The Land of the Big Red Apples" (47-51) | | | | —The "journey to the Red Apple Country"—on the "iron horse" (47)—it all sounds so "mythic"! | | | | —The white man's/colonizer's gaze ("glassy blue eyes" [47])—& the women's, and children's—upon our young Dakotas, to Z-Ša's embarrassment, even humiliation (47-48) | | | | —Humorous crack about the "low moaning" of the telegraph pole: "I used to wonder what the paleface had done to hurt it" (48; an innocuous aside that may have deeper resonances, given the later motif of the "machines" of Western Civ.). | | | | —Arrival at the school per se (White's Manual Institute, in Indiana)—to (the image/motif of) LIGHTS & whiteness: "lights"; "brightness"; "strong glaring light"; (even the) "whitewashed room" (49) and "white table" (50) | | | | —Caught and tossed in the air by the "rosy-cheeked paleface woman," Z-Ša "frightened and insulted": "My mother had never made a plaything of her wee daughter" (50). [Word choice: note "wee" as synonym for "little," another common self-reference motif.] | | | | —And so, like Babe the movie pig: "I want my mom!" [er, "mother!"]—and sobbing herself to sleep, with the phrase "wonderful land of rosy skies" sounding a little less glorious now. . . . | | | II. "The Cutting of My Long Hair" (52-56) | | | | —Initial setting = mood: "bitter-cold," "bare" trees, the "constant clash of harsh noises" (52; say that last phrase aloud!) | | | | —morning breakfast & prayer (52-54) = "eating by formula" (54) | | | | —Judéwin warns her of the hair-cutting to come; and "when Judéwin said, 'We have to submit, because they are strong,' I rebelled" (54). . . . so runs and hides, under a bed, in a "dark corner" (55) | | | | —Note the cultural differences, here ignored by the educators: shorn hair, among the Dakota, "only [for] unskilled warriors who were captured" and for "mourners" (54). [Ironically, she is in mourning, isn't she!?] | | | | —Found and "dragged out . . . kicking and scratching" (55)—and her hair finally cut: "Then I lost my spirit" (like Samson?!); oh, the indignity: "now I was only one of many little animals driven by a herder" (56; see buffalo comparison [10]; see also 45). | | | III. "The Snow Episode" (57-61) | | | | —Making body patterns in the snow forbidden (why?!); but the three Dakotas forget, and disobey (57). | | | | —Judéwin's ill-fated language lesson: just say "No"—which they practice on their way to questioning (57). . . . Oops, bad idea, for Thowin, anyway, who unknowingly answers "no" to the wrong questions—and a spanking (58-59). | | | | —Language/cultural barrier: "[M]isunderstandings as ridiculous as this . . . frequently took place, bringing unjustifiable frights and punishments into our little lives" (59). | | | | —Z-Ša's (first act of) REVENGE: the turnip (over-)mashing episode (59-61): "I felt triumphant in my revenge . . . . I whooped in my heart for having once asserted the rebellion within me" (60, 61). [Word choice: not the first time whoop has appeared; why use such a racially loaded term?!] | | | IV. "The Devil" (62-64) | | | | —The novelty of Christian dualism (God vs. Satan): "I never knew there was an insolent chieftain among the bad spirits"—the picture of which she is shown ("the white man's devil") (62). | | | | —And the threat: "this terrible creature roamed loose in the world" to torture "little girls who disobeyed school regulations" (67-68)! | | | | —DREAM of the devil and her mother (63-64): (humorous aside?:) "he did not know the Indian langauge [sic: typo]" (63) . . . . How do you "interpret" the dream's ending?: just as the devil was about to attack her, "my mother awoke from her quiet indifference, and lifted me on her lap. Whereupon the devil vanished, and I was awake" (64). | | | | —Another revenge—now, on the devil: in a book called The Stories of the Bible, "I began by scratching out his wicked eyes" (64). [Hmmm: remember other "eyes" in this narrative?] | | | V. "Iron Routine" (65-68) [aka Pink Floyd's "Welcome to the Machine"!?] | | | | —The title establishes an imagistic motif that "clangs" its way through this chapter of a "paleface day" of machine-like regimentation: the "loud-clamoring bell" (65; see also the "loud metallic voice" of the bell on p. 52); the pencil ticks of roll call: "It was next to impossible to leave the iron routine after the civilizing machine had once begun its day's buzzing" (66). | | | | —"Tamed ANIMAL": And so "I have many times trudged in the day's harness heavy-footed, like a dumb sick brute" (66). | | | | —Critique of medical care (another "mechanical" activity) (66-67): "Once I lost a dear classmate"; crying at the deathbed, seeing the open Bible: "I grew bitter. . . . I despised the pencils that moved automatically, and the one teaspoon . . . dealt out . . . to a row of various ailing Indian children" (67; recall Levchuk's essay on Indian boarding schools). | | | | —Her anger strikes out even against Christian indoctrination, "inculcating in our hearts . . . superstitious ideas" (67; woh!). | | | | —The "machine" continues: "I was again actively testing the chains which tightly bound my individuality like a mummy for burial" (67; see narrative's end [p. 99], where she wonders if such an education is really "life" or "death"). | | | | —Concluding retrospective on this trauma—and the (curious) final figure of speech: "The melancholy of those black days has left so long a shadow that it darkens the path of the years that have since gone by. . . . Perhaps my Indian nature is the moaning wind which stirs them now for their present record. But, however tempestuous this is within me, it comes out as the low voice of a curiously colored seashell, which is only for those ears that are bent with compassion to hear it" (67-68). Why does her angry "tempest" become the "low voice" of a "seashell"? Enforced suppression? Conscious audience consideration? A fondness for "purple-prose" images of nature & the exotic? | | | VI. "Four Strange Summers" (69-74) | | | | —Return home after three years back East—not many details for "four strange summers" back in SoDak/among her people?!—to the "heart of chaos," and an "uneducated" mother who cannot understand her. . . . (69) | | | | —In sum, ALIENATION, from her mother, her tribal heritage, and "Nature" itself: "Even nature seemed to have no place for me. I was neither a wee girl nor a tall one; neither a wild Indian nor a tame one" (69). | | | | —Buckboard joyride episode (70-72), and her re-appreciation of the vastness & beauty of the Great Plains: "Within this vast wigwam[!?] of blue and green I rode reckless and insignificant" (70-71); impulsively chases coyote (71). . . . | | | | —Dawée won't take her to the party, of "jolly young people"—Dakotas, all, who "had become civilized"; and Z-Ša, too, as she complains about not being "properly[!] dressed" (72-73)? | | | | —Mother consoles her—with "the white man's papers" (Bible)!; but she greets even this, now, with "rejection" (73; not TOO spoiled, eh?). | | | | —Then perhaps the most pathetic part of the narrative: her "mother's voice wailing" outside, and—"I realized . . . she was grieving for me" (74). WHY? | | | | —Now, "schemes of running away" from the Rez—oh, the irony!; the "turmoil" felt at home "drove me away to the eastern school" (74)! | | | VII. "Incurring My Mother's Displeasure" (75-80) | | | | —But some traditionalism still evident: from a medicine man, she brings "a tiny bunch of magic roots" with her, a charm to get friends; "Then, before I lost my faith in the dead roots, I lost" them (the roots) (75). | | | | —High school diploma earned, she moves on to Earlham College (Indiana) "against my mother's will" (75). . . . Versus her mother's hints that "I had better give up my slow attempt to learn the white man's ways, and be content to roam over the prairies and find my living upon wild roots" (75-76). [Not good enough for yu', now!?] | | | | —So, "homeless and heavy-hearted," back to school to—(more) racism: "among a cold race whose hearts were frozen hard with prejudice" (76). | | | | —Remember the Chrystos poem in which survival = making "pretty things"? Z-Ša, too, tries spinning "reeds and thistles," "the magic design of which promised me the white man's respect" (76). | | | | —ORATORY (76-80): 1st place at Earlham, to the overt praise of her fellow students (77-78); then the state (of Indiana) contest (78-80), where she experiences "a strong prejudice against my people" (78), evidenced in shouted "slurs against the Indian" and the flag "with a drawing of a most forlorn Indian girl"—and the word "'squaw'" (79). | | | | —Oh, the "barbarian rudeness" (79): note how Z-Ša, the author, reinscribes ("reinvents"!?) the word's original intent, as denotative of those who are not part of (Western) "civilization." Here the "civilized" are the barbarians, at last. | | | | —(Oh—she wins 2nd place.) | | | | —Another fit of vengeful thoughts upon winning her prize ("the evil spirit . . . within me") (79-80) . . . but back alone in her room, thoughts of home—and guilt: "In my mind I saw my mother far away on the Western plains, and she was holding a charge against me" (80). |

RESPONSE #2—Due TUES., 2/22 (uploaded to Canvas by midnight)—CHOOSE ONE (2 or more pages): RESPONSE #2—Due TUES., 2/22 (uploaded to Canvas by midnight)—CHOOSE ONE (2 or more pages):

—Don't worry about MLA formatting, headers, etc.; but do indicate which option you're doing, please.

a) As mentioned on the syllabus, one option is to turn in a do-your-own-thing "READER'S JOURNAL" that addresses a "goodly" range of the readings (that is, from Newcombe: "500 Years of Injustice" to Alexie's "Indian Education" [see below for full range]). (These should ideally be responses you wrote immediately after reading, so there's no danger of simply rehashing class ideas.)

b) Write your own evaluative "book review" of Z-Sha's 3-part boarding-school narrative (7-99). How well does she navigate the "caught between two worlds" dilemma spelled out on my intro PDF? (Alternative: write the review from the point of view of a well-intentioned [or not] east-coast Euro-American, circa 1901?!)

c) Alexie's "Indian Education" is a humorous 1990s short story written well after the heyday of boarding schools, land allotments, "Indian wars," and the like. Relate Alexie's story to at least TWO of our non-fiction/non-poem readings (from this range of readings), showing that the "historical trauma" of the Native experience is still evident in this humorous tale.

d) Rhetoric & TONE: obviously, there is a wide range of "tonal" choices available to the (Native or not) author writing about Native history and issues: discuss at least two of the authors (from this range of readings) in terms of their relative success in this regard. For example, "X's rehtorical choices are well done [and convincing, and/or moving], while Y's are an abject (& alienating) failure!"

e) Free (but focused) Response: develop your own topic-choice as a focused response on our historical/boarding school readings, dealing with at least three of the readings since Response #1 (that is, from Newcombe on; Z-Sha's 3-part memoir counts as only ONE text!).

f) [New/2022:] Compare and contrast the two boarding school narratives by Z-Sha (in American Indian Stories) and Standing Bear ("First Days at Carlisle"). You might consider tone, audience, etc., and of course the experiences themselves.

—Note: For all responses, please include p#'s in parentheses for any specific references to our texts. Also, please avoid simply rehashing ideas brought up in class or in my online outlines. Feel free to object to/expand upon these, of course, but above all, try to do "something else" that still demonstrates that you've done the reading.

—Note: The full range of texts for Response #2 is as follows: Newcombe: "500 Years of Injustice"; Wilkins: "A History of Federal Indian Policy"; Gonzales: "The Black Hills"; Eastman: "The Ghost Dance War"; Cook-Lynn: "New Indians, Old Wars"; Joy Harjo: "I Give You Back"; Louis: "Red Blues in a White Town the Day We Bomb Iraqi Women and Children" Zitkala-Sha: her 3-part autobiography (7-99; count as one text!), "America's Indian Problem" (185-195); Standing Bear: "First Days at Carlisle"; Devens: "'If We Get the Girls, We Get the Race'"; Giago: "Reservation Schools Fail"; Alexie: "Indian Education."

|

|

|---|

| —Found on Facebook today (2/19/22). The difference is that starlings didn't have a choice; they were imported by a Shakespeare aficionado, who wanted every bird mentioned by the Bard to have a presence in the "New World."(Of course, one might well argue that poor Euro-human immigrants didn't have much of a choice, either.) |

XIT: "Reservation of Education" (YouTube) XIT: "Reservation of Education" (YouTube) |

|---|

| —XIT was a Diné band of the 1970's, whose often "radical" lyrics made them a favorite of AIMsters (and like-minded college undergraduates like me!) |

TU, Feb. 22nd:: TU, Feb. 22nd::

| "An Indian Teacher Among Indians" [1900] (AIS 81-99) |

|---|

| | I. "My First Day" (81-84) | | | | —Though ill, Z-Ša refuses to go home, out of "pride," and the knowledge/guilt that her mother would say that "the white man's paper's were not worth the freedom and health I had lost by them" (81). | | | | —So further East ("toward the morning horizon" [81])—to Carlisle. . . . | | | | —Meets her "boss" (Richard Henry Pratt), who has heard of her oratory skills, but seems disappointed in her person ("a subtle note of disappointment" [83])—Why? | | | | —Ah: besides her physical illness, she's not a happy camper, with the "lines of pain on" her face, and a "leaden weakness" from "years of weariness" (84). | | | II. "A Trip Westward" (85-92) | | | | —Again, having ignored "nature's warnings," she's stuck in an "unhappy silence" (85). [This detachment from Nature will become a "theme."] | | | | —So(?) her employer's plan to turn her "loose to pasture," to send her back West—for more recruits (85)! | | | | —the home ENVIRONMENT again: the "vast prairie" whose clouds and grass "thrilled me like the meeting of old friends" (86) . . . | | | | —the white DRIVER, and Z-Ša's classist/elitist attitude towards him!?: his "unkempt flaxen hair," "weather-stained clothes," and "warped shoulders" (87) | | | | —Her mother's initial reluctance to run to greet Z-Ša issues from a mistaken assumption about the white fellow (88-89)—what is it? . . . Z-Ša clears things up: "'He is [just] a driver!" (89). | | | | —Z-Ša's mother's own assimilationist "compromises": e.g., her log cabin now has curtains (89)! | | | | —But to Z-Ša's suggestions that she make improvements(!), she tells of her extreme poverty, due to Dawée's loss of his job (90); we learn, in fact, that Dawée's been replaced by a white employee, and—irony—can no longer "'make use of the education the Eastern school has given him'" (90-91); and the reason for being fired?—speaking out, making trouble, trying "to secure justice for our tribe in a small matter"—oh, the "'folly'" (91)! | | | | —Z-Ša grows bitter at the news: to her mother's praying, she says, "'don't pray again! The Great Spirit does not care if we live or die! Let us not look for good or justice: then we shall not be disappointed!'" (92). [On one level, the Lakota/Dakota wakan tanka really doesn't "care"! But on another level, I suspect, Z-Ša is rebelling, at the moment, against some Christian/Native hybrid deity she has recently come to believe in, arriving here at a version of Stoic philosophy.] | | | | —"Taku Iyotan Wasaka" (92): taku (TAHkhoo) = something; iyotan (eeYOHtah[n]) = very, most; was[h]'aka (wash'AHkah) = strong | | | III. "My Mother's Curse Upon White Settlers" (93-94) | | | | —Z-Ša's mother complains of the "shrinking limits" of Yankton lands, because of a "whole tribe of broad-footed white beggars" whose lights she points out to her daughter (93); and so another warning: "'beware of the paleface,'" who "'offers in one palm the holy papers, and with the other gives a holy baptism of firewater'" (93-94)—[Vine Deloria never expressed it better!?]—who is "'the hypocrite who reads with one eye, "Thou shalt not kill," and with the other gloats upon the sufferings of the Indian race'" (94). [See the fate of the "The Soft-Hearted Sioux" for a similar irony.] | | | | —The mother's final gesture of a "curse," with "doubled fist" (94): rather too melodramatic, en'uh? | | | IV. "Retrospection" (95-99) | | | | —Z-Ša's final, earnest critique of Indian boarding schools; incl. her "indignation" about unqualified teachers—the "opium-eater," and the "inebriate" doctor who "sat stupid" while Indian students "carried their ailments to untimely graves" (95); the government inspection procedure, too, is inept; so at last, she concludes, "I was ready to curse men of small capacity for being the dwarfs their God had made them" (96)—what does she mean by this?! | | | | —Alienation/detachment from "Nature" encore—and traditional religion (and mother): "For the white man's papers I had given up my faith in the Great Spirit. For these same papers I had forgotten the healing in trees and brooks. On account of my mother's simple[?!] view of life, and my lack of any, I gave her up, also" (97). | | | | —Alienation continued—via remarkable TREE metaphor: "Like a slender tree, I had been uprooted from my mother, nature, and God. I was shorn of my branches. . . . Now a cold bare pole I seemed to be, planted in a strange earth. Still, I seemed to hope a day would come when . . . [I] would flash a zigzag lightning across the heavens" (97). Did this hope come true? | | | | —So—a "new idea": retirement from teaching (97-98); and the retrospective in earnest, thinking back on the "many specimens of civilized peoples," of "Christian palefaces" who were pleasantly surprised to see "the children of savage warriors so docile and industrious" (98; note, too, the emphasis on their "gazing"). | | | | —But finally, is this assimilationist education a good thing?—a question, she laments in the final sentence, that too few have pondered: "few there are who have paused to question whether real or long-lasting death lies beneath this semblance of civilization" (99). |

| "America's Indian Problem" [p. 1921, in The Edict] (AIS 185-195) |

|---|

| | —Z-Ša's well-chosen introductory examples: | | | | 1. The Jamestown Colony, and Captain Newport's erection of a "'cross as a sign of English dominion'"; and then his lie to Powhatan that the cross's "arms . . . represented Powhatan and himself, and the middle [of the cross] their united league" (185)! | | | | 2. DeSoto's forces stealing pearls from ancestral Native tombs [S. Carolina]—DeSoto says, "'to make rosaries of'"!; Z-Ša's source's hilarious commentary: "'We imagine if their prayers were in proportion to their sins they must have spent the most of their time at their devotions'" (186)! | | | —Z-Ša's conclusion (& complaint): "It was in this fashion that the old world snatched away the fee in the land of the new" (185). . . . Again she re-defines/inverts "barbarism" in the colonizers' "barbaric rule of might" (186). | | | —Appeal for Indian CITIZENSHIP/the VOTE: Natives, in contrast, are now but "legal victims," and "wards" instead of "citizens." . . . A CALL to ACTION—with the aid, you should note, of early-20th-c. feminist activism: "Now the time is at hand when the American Indian shall have his day in court through the help of the women of America" (186). . . . "Wardship is no substitute for American citizenship, therefore we seek his enfranchisement" (187). | | | —Point of View!?—who is the We in the bottom paragraph of 186?: "We serve both our government and a voiceless people . . . . We would open the door of American opportunity to the red man . . . " (186). . . . Then another PofV switch: "Do you know what your Bureau of Indian Affairs . . . really is?" (187)—NOW who's the you? | | | —The concluding lengthy quot., then, from the Bureau of Municipal Research report (1915): [This "story of the mismanagement of Indian Affairs" (193) reads like a nightmare from Kafka!] | | | | —"Prefatory Note" (188): while we spent a lot o' time on this report, it "is not available for distribution"! | | | | —"Unpublished Digest . . ." (188-): there has been no official govt. "digest of the provisions of statutes and treaties with Indian tribes governing Indian funds"—so we made one; but "it found its way into the pigeon-holes" of bureaucracy and remains "unpublished" (188-189). | | | | —"Unpublished Outline . . . (189-)": likewise, this "also found repose in a dark closet" (190)! | | | | —"Too Voluminous . . .[!]" (190): well, we coulda put a copy in the Library of Congress, "but the only official action taken was to order the materials be placed under lock and key in the Civil Service Commission"! | | | | —"Need for Special Care . . ." (190-)—because "in theory of law the Indian has not the rights of a citizen. He has not even the rights of a foreign resident. The Indian individually does not have access to the courts"; as a "ward" of the federal government, his "property and funds are held in trust" (191). [Note: besides Indian citizenship (1924), such government misgovernment led to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.] | | | | —"Conditions Adverse to Good Administration" (191-)!: translation—conditions are BAD!; lots of administrative misdeeds (192 ["fraud, corruption" (193)]). | | | | —"Government Machinery . . ." (192-): and lots of misappropriation of funds out of greed (192) | | | | —"Ample Precedents" (194-): Conclusion—"All the machinery of the government has been set to work to repress rather than to provide adequate means for justly dealing with a large population which has no political rights" (195). |

|

|---|

| At several points in her narrative, Zitkala-Ša reverses this civilization/barbarism binary. I also recall Silko claiming that both U.S. political parties play the "race card" ("The Border Patrol State" 121)—and here, the "primitivist" card. (Especially ironic when a POC does it.) Of course, the point above is how much (and how easily) the U.S. projects its own behaviors upon others. |

| Standing Bear: "First Days at Carlisle" (from My People, the Sioux [1928]) (Trout 598-610) |

|---|

| | ** Crucial (and usually sadly hilarious) passages: | | | | -*-Inception of the School: par. 7-9 | | | | -*-NAMING: 18-22 | | | | -*-WRITING: 23-25 | | | | -*-Clothes/Hair: 33-53 | | | | -*-Religion/Church: 55, 62-63 | | | | -*-Plate-painting: 60 (worth some $ now!?) | | | | -*-"Occupational therapy"—(and irony of trade as) tinsmith: 65-66 | | | | -*-(hilarious) Brass band episode: 68-71 |

|

|---|

—my response to an old student paper that

misspelled "Standing Bear" throughout |

Devens: "'If We Get the Girls, We Get the Race': Missionary Education of Native American Girls" (NAV 284-290) Devens: "'If We Get the Girls, We Get the Race': Missionary Education of Native American Girls" (NAV 284-290) |

|---|